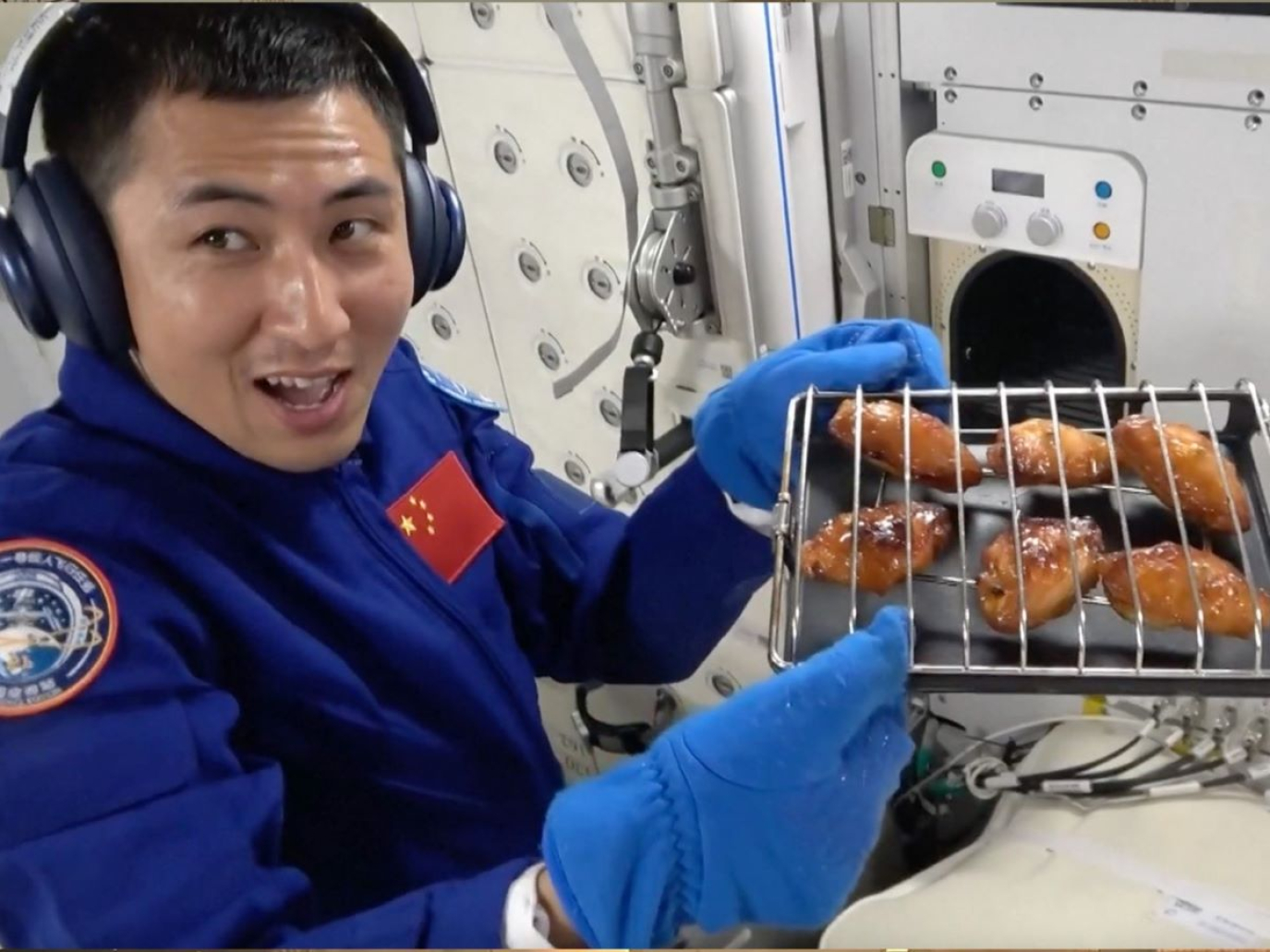

In a video released in November by the CGTN network, five taikonauts (from taikong: space in Chinese) are seen roasting chicken wings on board a space station. “This is the first time in the world that something like this has been done,” explains Liu Weibo of the China Astronaut Research and Training Centre to the broadcaster. “We inserted a filter inside the oven to absorb particulate matter and prevent air pollution in the station.” And the colour, scent and flavour – the taikonauts assure us, mouths watering – are spot on.

This scene straight out of an intergalactic cooking reality show appears to have been timed perfectly to prepare the ground for much more substantial announcements. On 29 January, during an institutional conference on aerospace in Shanghai, the Chinese government officially unveiled their strategy for the development of the space economy over the next five years: Space+, or rather 太空+.

As in Beijing's style, this is a full-on five-year plan that aims to bring together all the institutional, scientific and commercial sectors related to space into one coordinated framework: exploration, astronaut training, satellite constellations, digital space infrastructure and AI, data collection and monitoring of space debris, lunar and Martian bases, space mining and the production of energy or other resources outside Earth. And, yes, space tourism is also included. So it's best to prepare for the demands of Chinese space tourists and learn how to cook kaoji worthy of the name, even in orbit.

An ecosystem for the new Chinese space economy

The Space+ plan did not come out of nowhere, of course. For years, China has been investing in space research programmes and the development of groundbreaking technologies. And it will be remembered how, in 2024, the Chang'e 6 lunar mission was celebrated with considerable enthusiasm, as it succeeded in bringing back to Earth rock samples taken from the dark side of the Moon for the first time in history.

From Beijing's point of view, the space race in recent years has been experienced as a pursuit of the US rival. But now, buoyed by its many achievements in the field of technology, not least in artificial intelligence, the Chinese government is aiming to take the lead. And it is doing so in its usual way: by gathering all its resources, both institutional and private, and coordinating them within a unified framework to achieve its objectives.

The novelty is that, unlike past plans focused on national missions, the roadmap that is taking shape this time will be explicitly commercial, openly competing with the Western model. The state agency China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) will be leading this commercial rush to the stars.

From space tourism to satellite constellations

The hype surrounding China's space economy has undoubtedly been generated by CASC's announcement regarding the development of space tourism. The Beijing-based state agency has stated its intention to establish operational suborbital tourism within five years, followed by a gradual transition to passenger services in orbit.

While it may seem strange to picture the CCP planning Bezos-style excursions to send Katy Perry and friends into orbit, we must consider what else this type of market could enable at a structural level. As the Lexology think tank explains, the development of human transport vehicles requires high safety standards for crew, ad hoc insurance markets, ground infrastructure and regulatory frameworks for commercial space flights. Most importantly, reusable launch systems are needed to make it economically viable. All these aspects, particularly the latter, are of interest to Beijing. In its rivalry with the United States, China's Achilles' heel is that it has not yet succeeded in completing a test launch with a reusable rocket.

On the contrary, as the Singaporean newspaper The Straits Times writes, “US rival SpaceX’s Falcon 9 reusable rocket has allowed its subsidiary Starlink to achieve a near-monopoly on low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites and it is also used for orbital space tourism.”

Musk's satellite monopoly is regarded by Beijing as a risk to national security, and that is why, according to The Straits Times, China is reportedly preparing ambitious plans to put 200,000 satellites into orbit by 2040. But to do so, launch costs must be reduced, and rocket reusability is key.

To the moon and beyond

The prospects of the Space+ plan, however, look far beyond the crowded orbit around Earth. First of all, China intends to develop actual digital space infrastructure, with artificial intelligence platforms capable of processing data directly in orbit. This would allow the continuous and more intense solar exposure to be exploited to generate the energy needed for highly complex calculations without burdening terrestrial networks. Indeed, this is a subject that Western companies, starting with SpaceX, are already discussing. Yet the integration of orbital computing into Chinese industrial planning will certainly raise new questions about cybersecurity and data governance.

Another interesting point concerns the development of in situ space resources. In practice, in order to build permanent lunar bases, or even Martian bases, that would be independent and sustainable, it will be necessary to ensure energy generation and extract resources from the lunar soil itself (which could perhaps also be brought back to Earth).

Lastly, it is certainly no coincidence that the presentation of the CASC's plans came just two days after the inauguration of China's first School of Space Exploration at the Beijing Academy of Sciences. “The next 10 to 20 years will be a window for leapfrog development in China’s interstellar navigation field,” writes the government press agency Xinhua. In short, after operations in Earth orbit and on the Moon, China is aiming for deep space exploration.

Cover: a frame from the CGTN video