Why talk about food and the circular economy?

Linear management, that has characterised the food production and consumer systems over the last century, has been the root cause of environmental and social degradation. It has contributed to the depletion of natural and cultural assets, generated pollution from the field to the stomach and often producing poor food, both in terms of nutrients and values. This economic system has demonstrated how mankind can become greedy, causing disruption to the natural balance by extracting resources from ecosystems and sifting them back into natural cycles. Food waste and losses are a good case in point. Indeed, they represent 1/3 of the entire production of food, and could feed the 795 million people that are currently starving 4 times over.

So, it is pretty clear that the relationship between humans and nature is no longer founded on a win-win rationale – i.e. aimed at the mutual satisfaction of players within the same system – but rather a lose-lose situation, where both humans and ecosystems are losing out on their chances of survival.

The potential impact and benefits engendered in a shift towards a circular and systemic rationale are humongous: enhanced stability and healthy ecosystems, a recovery of the ability to share, cooperation, as well as becoming consciously responsible and reaping the benefits of widespread wellbeing. To date, technological development and dissemination of knowledge have indeed led mankind to a point where we are able to feed over 7 billion people. In contrast, it also leaves the next generations a not too promising and already compromised global situation.

This is why the circular economy must be seen as the right “diet,” in reference to the etymology of the word diet, which comes from the Greek diaita, meaning “a way of life.” Food has a unique and incomparable strategic potential within the productive sector. Food feeds our bodies as well as the nature of our relations with the world and other people. Therefore, food can embody circular economy principles whilst at the same time bolstering the circular economy by outlining a theoretical and practical course of action and defining its objectives.

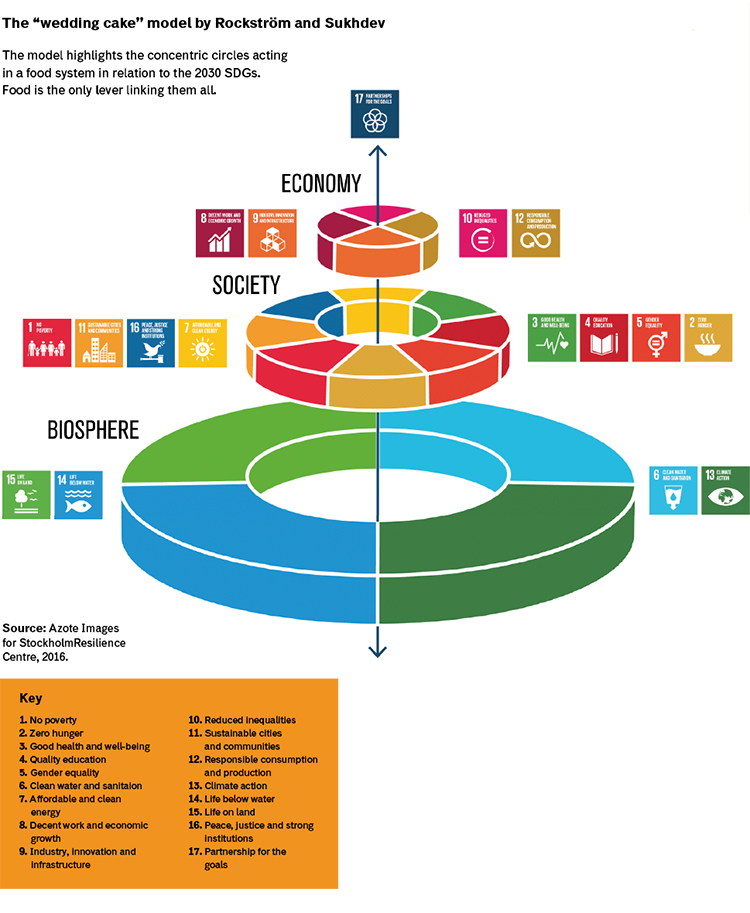

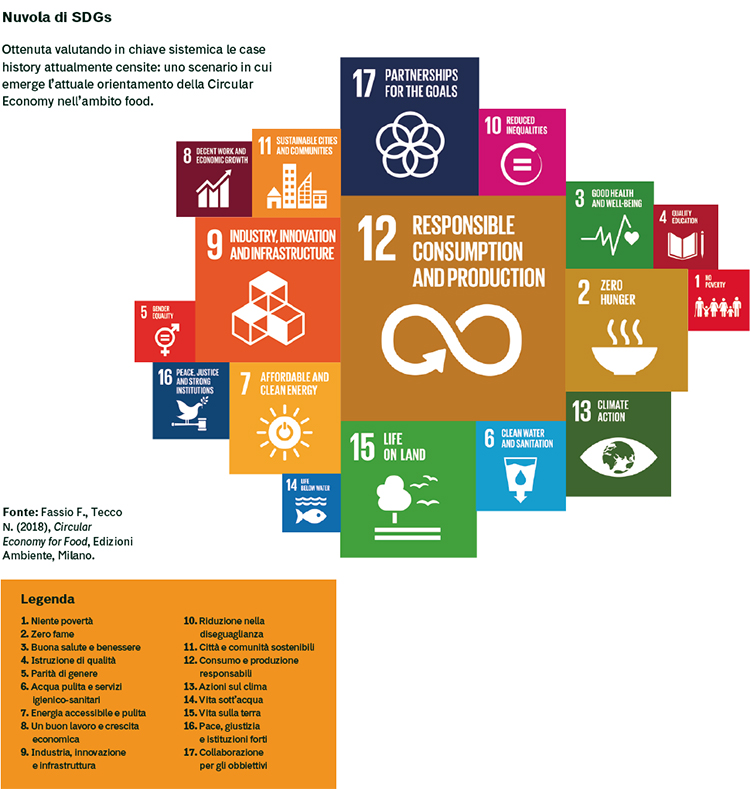

Therefore, in an aptly-oriented food system, the circular economy can find a precious ally that can help achieve many, if not all, UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as well as propel the development of many emerging economies and improve the agricultural sector in industrialised ones.

The bearers of change

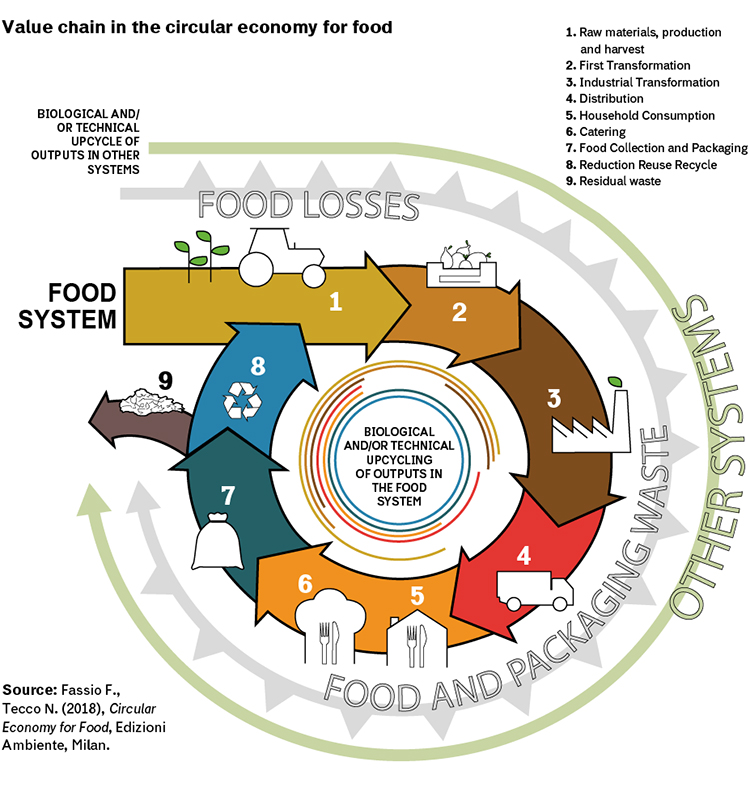

In practice, how does the circular economy materialise in the food system? One of the answers comes out of the research group “Circular Economy for Food. Materia, energia e conoscenza in circolo” (Circular Economy for Food. Materials, energy and knowledge in circulation) of the University of Gastronomic Sciences in Pollenzo, Italy. Their research has led to the classification of over 150 international and national case studies, some of which are included in the homonymous book published by Edizioni Ambiente and mentioned again in the current “Focus” section in Renewable Matter.

Although dealing in experiences that have big variations between them due to company sizes, positions within the food system, types of product, secondary materials or services used for circular action (from corn cobs to beet molasses, and from olive pomace to nut shells, as well as taking into account the specific characteristics of materials in the complex food system), the analysed experiences of circularity revolve around two key words: upcycling and eco-design.

Upcycling represents the transformation of what is wrongly considered waste or of little value into a new resource for another productive or consumer cycle. Unlike what traditionally happens with recycling processes, where materials often experience a loss in value (downcycling), the material/immaterial and/or relational value is kept or even enhanced, while reducing disposal costs – where possible – especially with regards to special waste that is subject to specific legal regulations. This is the case with Duedilatte and Vegea that obtain textile fibres from milk and wine by-products respectively. Upcycling is also the procedure carried out by Frumat company, whereby apple peel and cores become paper; or when hazelnut shells are transformed by Agrindustria into plant granules for vibratory finishing, polishing and sanding procedures or, as they are used by Ferrero, in the production of packaging cardboard and to extract probiotic fibre.

The other key word is eco-design. Here, we are dealing with a decision: to use “circular” resources because they are reusable, some of which in (almost) endless cycles, such as glass and steel for packaging; to prefer renewable material and energy resources; to keep purity of resources throughout the various stages of the value chain; to favour single-material use and stop material contamination or to adopt new technologies that endorse disassembly and recovery operations; and to promote sharing practices. Proximity takes on a new value, both in the rational use of locally-available resources and in the search for creative solutions for their uses, as well as the value attached to the relations of local industrial and territorial symbiosis. In this respect, the non-alcoholic drink Unico is a good example. It is produced by Lurisia Acque Minerali with 70% of Barbera grapes and 30% apple juice, and mashed pears and peaches. The case study represents the potential of circularity in finding answers to local needs, such as the market crisis faced by Piedmont Barbera grapes, which might otherwise have been left unpicked, since the costs of picking them was too high compared to the revenue generated with their sale. The Unico drink production took place between 2013 and 2016, up until the Barbera grape market stabilised again, thus showing the value of circularity and its ability to adapt to temporary situations that would otherwise engender food loss and waste.

In essence, markets all over the world show how companies are increasingly moving towards generating new relationships of symbiosis, which is synonymous with shared responsibility, and towards the creation of new opportunities for development and jobs. The concept of product quality is progressively evolving throughout the whole production chain and over time redefining the terms of agreement between consumers and producers, and towards a new paradigm for the creation of more integrated economic, social and environmental relations.

Thanks to the Circular Economy for Food, a context is gradually forming whereby the concept of “system quality” and “value system communication” will develop against a background that must move on from an industrial to a communication symbiosis. Therefore, agro-economics must increasingly take into consideration the value chain of resources in view of circularity within open systems (food systems), thus helping the development of peoples’ food sovereignty, and by taxing resources rather than work. The circular economy, associated with food topics, is a great opportunity that can wholly rethink the Green Revolution and restore the marriage of two players in the same system, food and humans, in sickness and in health.

F. Fassio, N. Tecco, Circular Economy for Food, Edizioni Ambiente 2018; www.edizioniambiente.it/libri/1197/circular-economy-for-food

The Impacts of Linear Agriculture

Food production is one of the main causes of the world’s loss in biodiversity. This is due to its impact on natural habitats and overexploitation of certain species. According to FAO estimates, 75% of crop varieties have been lost and 3/4 of global food depends on just 12 plant and 5 animal species. Such agro-biodiversity loss directly affects food: out of 30,000 edible plant species present in nature, there are just 30 food crops that alone account for 95% of the world’s energy requirements. These include wheat, rice and corn, and supply over 60% of the calories we consume. Industrial agriculture based on intensive production, monocultures, a restricted number of plant and animal species, and external synthetic inputs (such as fertilisers and pesticides) account for almost 34% of the planet’s total surface area and almost half of the inhabitable land. It is estimated that agricultural production is responsible for 69% of water extraction and because of that, by 2030, almost 3 million people will not have easy access to drinking water. Together with other players in the food system, agricultural production is responsible for almost 30% of greenhouse gases. Out of 1.5 billion hectares of farmed land worldwide, 1/3 is used to produce animal feed while the remaining 3.4 billion hectares are used as pastures. However, animal-derived products represent only 17% of calories and 33% of protein consumed by humans around the world. Due to intensive farming, 25% of the planet’s soil is severely depleted and 30% of arable land has become unproductive. If we consider population growth estimates, that predict the world population will exceed 9 and a half billion people by 2050, this “target,” coupled with current consumption patterns, will require a 70% increase in agricultural production.

In this production framework, every year, 1 billion and 300 million tonnes of food for human consumption goes to waste, totalling the equivalent of almost 8,600 cruise liners worth of food waste. At a global level food waste has an economic value, together with the estimated costs linked to the environment and society, of $2,600 billion a year.

The rate of risk of mortality due to diseases related to a poor diet exceeds that of diseases caused by insufficient calorie intake. While there are 795 million people starving, about 1.5 billion people are obese or overweight. Worldwide, about 36 million people die every year from lack of food, whereas 29 million die from diseases linked to overeating.

When we are faced with the fact that $267 billion a year would be sufficient to eliminate world hunger by 2030, amounting to approximately 0.3% of the world’s GDP, we are quite obviously witnessing a genuine “crisis of reason.”

CASE HISTORY: BACARDI

An innovative step towards overcoming such issues was taken by Bacardi, world leader in the production and distribution of alcoholic beverages. Bacardi has adopted many measures over the years to reduce its own environmental impact, focusing on energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. With Vodka 42 Below, Bacardi Group launched an innovative campaign for the recovery of citrus fruit and olives from cocktail glasses in Australia and New Zealand. Bars serving them collect the organic matter which would otherwise be landfilled, pile it up and hand it over to Bacardi. In 2016, three months on from the start of the initiative, 400 kilograms of organic matter, from 3,200 cocktails, were recovered. This then went towards creating 20,000 single-use soap packages and over 400 mid-sized dispensers which were then redistributed to the bars involved.

Citrus fruit and olives are actually used as basic ingredients for several cosmetic products and detergents thanks to the essential oils extracted from fruit zest or pulp. The recovery of such waste responds to consumer needs and in particular to those of the cosmetic industry that can thus, for instance, extract the aroma from the peel of real lemons instead of using synthetic substances. Thanks to the collection of waste, over just two weeks and with good customer attendance, a bar can contribute to the production of an average of 25 litres of soap.

CASE HISTORY: BALADIN

Baladin brewery was initially founded in 1996 in Piozzo as a simple brewpub. Since 2012 Baladin has become a farm brewery in its own right. The new brewery – inaugurated in July 2016 with a production capacity of 50,000 hectolitres – focuses on respecting the local economy and the efficient use of raw materials, with special attention to regeneration of waste and the use of energy produced with renewable sources. Baladin intends to pursue a “production autarchy” model in every step (with the exception of some spices), so as to reduce their environmental impact, taking on responsibility for the entire production cycle of its beers and with the ambition of reaching full autonomy with regards to the main raw materials used.

Since 2016, the company has directly managed a 1 hectare plot of land, 800 metres away from the brewery in the municipality of Piozzo. For their “circular” energy independence, the distribution headquarters supplies its energy requirements with 1,800 square metres of solar panels, whereas the brewery is run on certified energy from renewable sources such as wind power.

The company is currently carrying out several trials to plan a “zero waste” production cycle, where waste becomes a source of energy or secondary material for new products. Starting from the production of one tonne of distillation residue per day from the brewing processes, on top of the usual option of upcycling them as livestock feed and fertiliser, a biomass-fuelled plant for generating heat is also being designed starting from dehydration and combustion of residues. Further experiments are leading the company to consider the possibility of producing other food products such as biscuits from distillation residues.

CASE HISTORY: LAVAZZA

Turin-based Lavazza, a leading company in the production of coffee, has developed a compostable capsule in collaboration with Novamont, operating in the bioplastic sector. Starting in 2010, the project required over 5 years of trials focused on the research of a high-performing material which could replace commonly-used plastics. A compostable plastic for Italian espresso coffee was created with Mater-BI, a completely biodegradable bioplastic obtained from plant components. Once used, the new capsule can then be disposed of with organic waste and sent on for industrial composting: after about 75 days, when the process of biodegradation is complete, there is a total transformation of the initial organic substances into simple inorganic molecules, thus making soil compost out of both capsules and coffee dregs. Therefore, compostable capsules also become an incentive to separate household organic waste.

The attention devoted to the capsule’s end of life thus contributes to further reduce the quantity of waste produced and to consolidate the company’s commitment in optimising packaging and processes within a circular perspective. Something which Lavazza has been doing for many years.

CASE HISTORY: LUFA FARMS

Lufa Farms is reinventing a broken food system by using urban rooftop spaces to produce food that can then be sold locally. The Canadian company, based in Montreal, is integrating food development into the urban fabric. A crucial element in bringing our linear food chain into a circular system.

In fact, since 2009, Lufa Farms has been tackling a variety of issues with their urban rooftop greenhouses. Not only do they make acres of unused rooftop space productive, they also take advantage of this position for collecting rainwater; harnessing free energy from the sun; using heat that rises from the buildings below; and lowering transport costs by taking “locally produced” to a whole new level and employing electric cars for deliveries. Lufa Farms have already built three rooftop greenhouses, amounting to 3.7 acres of growing space, where 1 acre of roof space can feed 2,000 people using 50% less heating energy, and 50-90% less water and nutrients. The greening of city roofs is going hand in hand with the circularisation of the urban food chain and Lufa Farms embodies a distributed and integrated approach to food production that will form the backbone of the circular economy.

CASE HISTORY: AGRIPROTEIN

The South African based company Agriprotein, founded in 2008, uses insects to produce high quality protein feed from organic waste. They are addressing the challenge of over 650 million tonnes of organic waste produced every year in cities, a figure that is likely to double by 2050. At the same time, they are also tackling the inefficiency of our food system, and in particular the way in which we produce our meat. By drawing on naturally occurring processes they have created a circular solution to organic waste and the production of animal feed.

In fact, Agriprotein uses the exceptional nutrient recycling capacity of the black soldier fly larvae to break down organic waste and at the same time produce high quality protein that can be used as animal feed. Furthermore, the residues left from this process are then used as rich compost. A truly circular solution! Agriprotein is a booming company, that plans to build 200 new facilities by 2027. The financial rewards of this model come hand in hand with reduced carbon emissions, regenerated soil and less pressure on wild fish stocks as a source of animal feed. Agriprotein believe that how we treat waste and how we produce our food are key factors in creating a truly circular food system.

From Gastronomic Sciences to the Food Monitor

by Andrea Pieroni, Luisa Torri, Michele F. Fontefrancesco

|

|

Andrea Pieroni

|

The end of the twentieth century has signalled a profound change in the perception of food in public debate. The aftermath of WWII was characterised by a rapid industrialisation in the agro-food sector and the establishment of mass consumption, creating a gastronomic landscape of unprecedented abundance. The decades of reconstruction signalled, for the most part, a rapid abandonment of traditional cooking and the erosion of local bio-cultural diversity, in the face of an affirmation of mass consumption of industrial products and an economic model far from any kind of sustainability. In relation to this massification of consumption and standardisation of taste, associations and movements arose during the eighties that were interested in the rediscovery and valorisation of local gastronomy and quality food. Amongst these: Slow Food.

A new consciousness of food

This cultural climate opened up a space for dialogue on the sustainability of food, a conversation that has rippled into present day. It reinforced the awareness that discourse on food and gastronomy needed a transdisciplinary synthesis, a community and a place where a new language and way of thinking about food could mature, so that challenges such as sustainability, the “good, clean and righteous,” the issue of food sovereignty and equal access to resources could be tackled effectively.

Out of this idealistic push, in 2004 the University of Gastronomic Sciences (UNISG) was born. Founded in Pollenzo, Italy, as a Slow Food initiative and with the collaboration of the Piedmont and Emilia Romagna regions, the University proposes a new methodological and didactical approach that is able to provide a complete vision of the systems of food production and form new professional figures with the necessary knowledge and transdisciplinary competences, tied to the agro-food industry, so that they can work to direct production, distribution and consumption of food towards sustainable choices. Today, UNISG is directly involved in guaranteeing high quality education and contributing to the sharing of knowledge to reinforce sustainability and food sovereignty around the world, promoting research that is able to contribute to wellbeing, the support of bio-cultural differences, and the recognition of the equal dignity between scientific knowledge and traditional knowledge.

The University’s research has moved towards a definition of “gastronomic sciences.” As the Manifesto di Pollenzo explains, drafted by the University, these are understood by the UNISG as a plural expression of all knowledge, methodology and practices that are applicable and inherent to food, and outline: “a new type of humanism [...that in line with] the best humanistic traditions places its roots in respect of the living and the blossoming of diversity at all levels.”

The UNISG’s approach to research is interdisciplinary and based on three interconnected macro areas of interest.

1. Bio-cultural diversity and change;

2. Quality and perception of food;

3. Environmental and economic sustainability.

The UNISG contribution

In this context we can address UNISG’s endeavours in the circular economy field. This concept is applied to the complexity of food systems and is crucial for the spread of a new concept of food innovation, tied to the safeguarding of natural, social and cultural capital and the right of all people to heathy and culturally appropriate food, produced using ecological and sustainable methods.

In this field of research there are new areas being developed. Amongst these is the study of the impact of circular economies on the performance of companies, sociological investigations on the perception of circular actions on society, the deepening of the “Circular Geography” thematic and its impact on specific areas, the analysis of the role of food in circular and regenerative cities, the valuation of acceptability and sensorial perception of new circular products on behalf of consumers, and the development of the Circular Economy for Food (CEFF) indicator with which to measure the impact of circular actions.

With regards to the accessibility of research, the university intends to make available all results, to both companies and society in general, on a dedicated digital platform: Circular Economy for Food Monitor. Therefore, the initiative wants to allow information to become knowledge and consciousness, making UNISG a point of reference on an international level for the theoretical and practical development of CEFF, a protagonist in the constant monitoring, analysis and planning of circularity in the food system.

University of Gastronomic Sciences of Pollenzo, www.unisg.it

|

|

Bottom: Universtiy of Gastronomic Sciences of Pollenzo. Source: Unisg

|

Andrea Pieroni is the Dean of the University of Gastronomic Sciences, and a Professor of Food Botany and Ethno-botany.

Luisa Torri, is an associate professor of Sensorial Sciences and Director of Research at the University of Gastronomic Sciences.

Michele F. Fontefrancesco, teaches Cultural Anthropology and is a member of the Research unit at the University of Gastronomic Sciences.