This article is also available in Italian / Questo articolo è disponibile anche in italiano

In November, COP30, the United Nations climate summit, will take place in Belém, a Brazilian city of 1.3 million people located on the Amazon River estuary. It marks a historical moment for international climate diplomacy following the failure of the “fossil” COP in Baku, and for Brazil, which wants to highlight its environmental progress under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. However, the country will be unable to hide its contradictions.

Lula, a leader in the climate fight?

The diplomatic opportunity for the South American giant is a tempting one. Brazil is an important mediator between wealthy and developing nations in climate negotiations, explains Claudio Angelo, former journalist at the respected Folha de S.Paulo and now communications coordinator at Observatório do Clima, a network of 77 NGOs. Saving the fight against climate change, despite the current geopolitical context and the stance of the United States, and unlocking resources for poorer countries would be a success.

Lula, who returned to office in 2023 with the ambition of making Brazil a “leader in the fight against the climate crisis”, has marked a sharp break with the denialism of his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro. “It was like going from hell to heaven,” says Caetano Scannavino, climate activist and coordinator of the NGO Projeto Saúde & Alegria, which has been active in the Amazon for nearly 40 years. “The Lula government, together with Marina Silva (a veteran environmentalist now back as Minister of the Environment, editor’s note), has reinstated the environmental, conservation and Amazon protection programmes that were scrapped during the Bolsonaro era.”

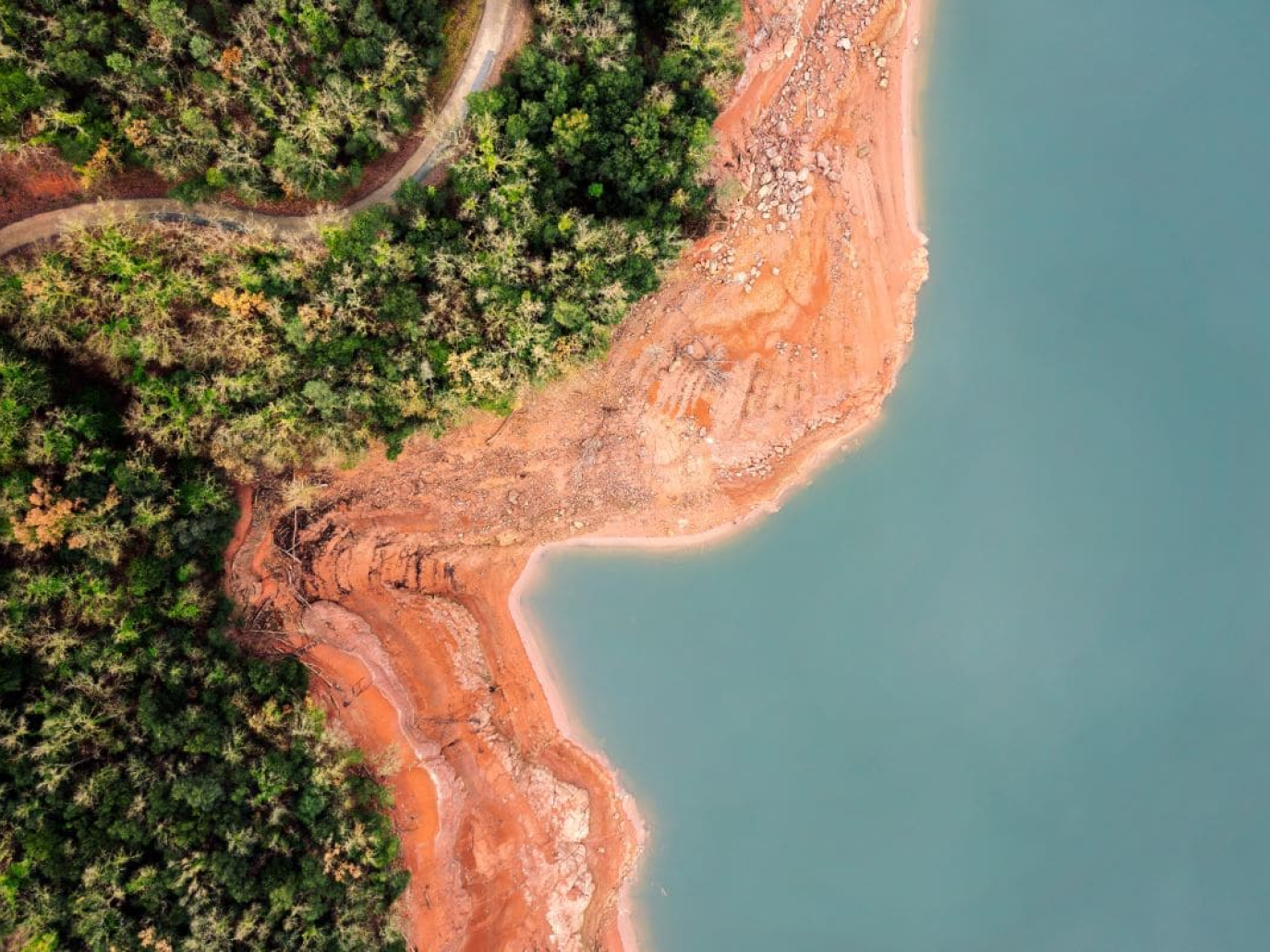

Deforestation in the Amazon has fallen by 46% in two years. But wildfires, fuelled by climate change, are increasing; deforestation in the Cerrado, Brazil’s savannah, is advancing at twice the pace of that occurring in the Amazon. And if infrastructure projects like the BR-319 highway—which cuts through 408 kilometres of Amazon rainforest in the states of Rondônia and Amazonas—go ahead, as the transport ministry intends, “we can say goodbye to any control over deforestation,” says Claudio Angelo.

Two Faces

The government and presidency present themselves as champions of the environment. Yet the Ministry of Agriculture subsidises the conversion of pasture into soybean cultivations and does nothing to prevent the illegal occupation of public land. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Mines and Energy is opening new oil and gas fields in the Amazon rainforest and offshore areas—including plans for drilling at the mouth of the Amazon River, near Belém.

Just months ahead of COP30, Brazil is showing a double face. On one hand, it is a champion of renewable energy: 90% of its electricity comes from clean sources, primarily hydroelectric, with a biofuels programme also in place. On the other hand, it continues to focus on oil. Petrobras, the state-owned oil and gas company, ranks 21st among the 36 firms responsible for half of global fossil fuel emissions. Its 2025–2029 plan allocates more than 70% of investment to the exploration of new oil deposits, while just 15% will go to the energy transition. There is no concrete plan to move away from oil, a key source of government revenue. The argument—supported by government officials—is familiar: the money is needed to finance the transition. But money is being made by obstructing the energy transition and putting the country and the planet at risk.

Deforestation and agribusiness

Scannavino notes that implementing bold environmental policies is no easy task with a Congress heavily influenced by the agribusiness lobby. Bolsonaro may have lost the election, but “bolsonarism” remains strong, representing roughly a third of the electorate, around the same segment of the population that sided with Lula. The remaining third is up for grabs.

Brazil’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), which sets out a 67% reduction in emissions by 2035 compared to 2005 levels, is hardly ambitious. The Climate Action Tracker observatory rates it as “almost sufficient” for meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement, but warns that the 2025 and 2030 targets are likely out of reach, and the pledge to reach net zero by 2050 remains vague, with no practical details and without a clear change on deforestation (and towards reforestation) and land use.

The growth of the biofuels industry is also a cause for concern. In Brazil, they account for 25% of transport fuels, a share that is growing. But the bioenergy boom is fuelling demand for land to grow crops such as sugarcane, soy, and palm oil, driving up pesticide use, creating deforestation, and taking land away from Indigenous Peoples. From this perspective, the success of RenovaBio, the national biofuels programme launched in 2017 and operational since 2020, is troubling. The state of Pará has a high percentage of degraded forest areas occupied by the palm oil agro-industry.

The Amazon could still be spared by agribusiness, explains Claudio Angelo, “Brazil has around two million hectares of already deforested land available for use. There is no need to fell a single tree to expand agribusiness. What is needed are investment and enforcement of the law.”

The People’s summit

Keeping a close watch on COP30 will be the 20,000 to 30,000 participants expected at the Cúpula dos Povos, the people’s summit organised in Belém by more than 400 social movements. Discussions will focus on climate justice, food sovereignty, Indigenous rights, and a just transition. Activists are united and determined to make their voices heard. Among the demands are the exclusion of fossil fuel lobbyists from the official COP30 negotiations and an end to “false solutions”, such as carbon markets and geoengineering.

DOWLOAD AND READ ISSUE #56 OF RENEWABLE MATTER: GLOBAL SOUTH

Cover: Envato image