The Fourth Plenum of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party has concluded in Beijing. For four days, from 20 to 23 October, the CCP leadership convened in what is traditionally a time to discuss internal party matters, but which had an exceptional nature this year: the focus was on the economy, and in particular the new five-year plan, the fifteenth (2026-2030).

According to many observers, the anticipation of the plan's themes, to be officially launched in early 2026, is due to the need to send a signal of confidence in a rather uncertain geopolitical and economic situation, between the tariff war and the domestic consumption crisis.

Therefore, it is no coincidence that, on the same day that the Plenum began, the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics published the latest GDP figures. The data show a 5.2% year-on-year growth in the first three quarters of 2025, with an acceleration of 0.2 and 0.4 percentage points compared to the growth rates for the whole year and the same period in 2024.

All in all, a confidence boost that sparked discussion about what appears to be a new chapter in the development of the Chinese economy: no longer based simply on speed, but centred on quality, internal security and stability. A strategic resilience plan.

The guidelines of the 15th Five-Year Plan

Triumphantly delivering 5.2% GDP growth (compared to the struggle to achieve the long-awaited 5% at the end of 2024), the Chinese leadership can happily announce the end of five years of “extraordinary development for the country,” as stated in the official statement. And this despite “rising protectionism, supply chain restructuring, and frequent regional conflicts… external ‘headwinds’ have been stronger than expected,” as noted by the Global Times. A result – adds the CCP's English-language newspaper – that “reinforces confidence in China's own development path. More importantly, it reflects a form of structural resilience.”

Precisely this structural resilience, according to Xi Jinping's indications, will be the focus of the fifteenth five-year plan: it will bridge the gap between the accelerated development of recent years and the achievement of the ultimate goal, the famous “modernisation” of China by 2035.

The guidelines remain more or less the same as those we have grown used to hearing in recent years: high-quality development and “new productive forces” (xin sheng chanli), to strengthen China's path from “world factory” to exporter of cutting-edge technology; pursuit of scientific and technological self-sufficiency, becoming increasingly urgent given recent developments in artificial intelligence research and US restrictions on chips; the centrality of the Beautiful China Initiative, and therefore a push for green transition and renewable energy as drivers of growth; strengthening domestic consumption and the domestic market.

Strategic resilience

To the “classic” guidelines, a general and marked emphasis on internal security has now been added, meaning military security, but also, and perhaps above all, economic security, in order to reduce dependence on exports and be less vulnerable to duties and unpredictable tariff storms.

Xi Jinping already announced this new course for Chinese development on 30 April, during an economic symposium in Shanghai: national security, not growth, will now be the central organising principle of economic planning, embedding key concepts such as resilience, technological sovereignty and risk mitigation. China's power, wrote the Jamestown Foundation think tank at the time, “is transitioning from growth-maximisation to strategic endurance.”

It does so, as mentioned, by focusing on high-tech sectors, from AI to semiconductors, from aerospace to renewable energy, and shifting its development from “competing in speed” to “competing in quality”, as reported by the Global Times. At the same time, however, the People's Republic remains firmly grounded: “At present, China remains in a phase of development,” says the official statement, partly to dispel speculation about a change of status in international frameworks, following the recent renunciation of “special treatment” in the WTO. In any case, it does not appear that the country intends to abandon its role as a global manufacturing giant.

“Xi has also made it clear that he does not want to abandon low end manufacturing (textiles, apparel, footwear, and so on), which normally happens when countries modernise and move up the value chain,” writes Eric Olander, director of the China-Global South Project, on LinkedIn. “One of the key lessons that Xi has no doubt learned from watching what’s happened in the U.S. and Europe in recent years is that when countries de-industrialise, it provokes political upheaval and a populist backlash. This is particularly salient now for China as the economy continues to show significant signs of strain, particularly under and unemployment.” And Xi does not want to take any risks, given the situation of deflation and underemployment that China is experiencing.

However, concludes Olander, “All of this is bad news for lower and middle income countries that have long dreamed of following China's development trajectory, which will now be much more difficult, if not impossible, so long as China insists on producing toasters and sneakers alongside semiconductors and drones.”

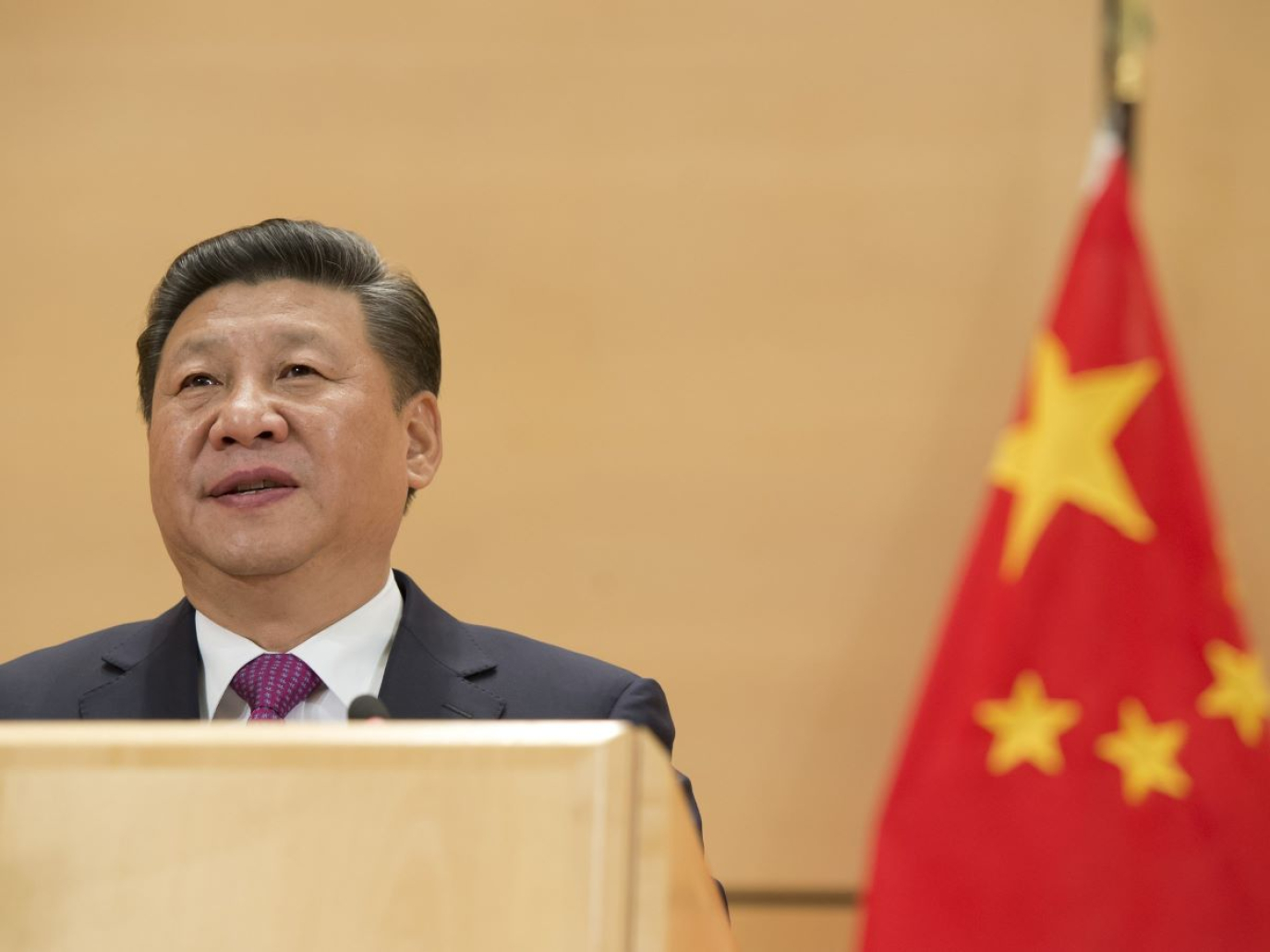

Cover: Xi Jinping, photo by UN Ginevra