This article is also available in Italian / Questo articolo è disponibile anche in italiano

The oblivion of death is a vertigo that we reject throughout our lives. But if, in De senectute, Cicero reflects on how men must accept the inexorable passage of time, for some years now, a growing array of doctors, biohackers, economists, nutritionists, and wellness experts have been declaring war on the obsolescence of the body – and mind.

From genetic medicine to artificial organs, from assistive robotics to chips that monitor the body’s biorhythm, and even to almost science-fictional solutions like cryogenisation and neural implants, the knowledge and devices for longevity and healthy aging are revolutionising the economy, the environment, and, most importantly, the global demographic landscape.

By the end of the century, the global average life expectancy will reach 83.7 years for women (up from 48.4 in 1959) and 79.8 years for men (up from 44.8), with peaks of over 100 years in some of the richest and most developed countries. In China and Japan, the average will even reach around 95 years of age, surpassing Southern Europe (92.07) and North America (89.45).

Understanding which devices and what knowledge will form the basis of this healthy longevity – living longer and being well is the axiom – and how to extend it far beyond the current genetic limits of about 120 years of age is the theme of this issue of Renewable Matter. In the following pages, we will explore the technologies for aging (age tech), wellbeing (health tech), and improving our quality of life (human tech).

We investigated the development of cryogenic preservation technologies with Alcor Foundation CEO James Arrowood; brain emulation research with neuroscientist Randal A. Koene; the economics of longevity with NICA Director Nicola Palmarini; genetic medicine, work, and assistive exoskeletons with market leaders like Comau and Hypershell; 3D organ printing and biofabrication, and neural chips to assist people with disabilities or for operational purposes, like a chip implanted in the hand for payments.

We even looked at medicine in space, both as an innovative technology and as a tool for understanding the human body’s behaviour in extreme conditions, in an era where discussions about Mars exploration are resurfacing. The pharmaceutical and nutraceutical world offered many options for study and reflection, but we chose to focus on the most discussed drugs of recent years: semaglutide-based medications like Ozempic and Wegovy, and the upcoming anti-obesity pill based on orforglipron.

Every door that opens reveals a fascinating and dynamic world, but one that often hasn’t even begun to study the environmental, economic, and social impacts of these technologies. From the perspective of sustainable economics, this means that each individual will have an increasingly larger ecological footprint. Both for the longer lifespan and the introduction of new health tech, such as exoskeletons, neural chips, assistive robots, and various wearable devices.

Will we have enough critical raw materials to provide democratic access to these systems? Will technologies be industrialised and optimised for widespread benefit, or will they remain a privilege of the wealthier classes, creating class-based longevity mechanisms? And again, what new technologies, drugs, and processes will we be able to invent thanks to AI, space tech, neuroscience, genetic medicine, and gerontomedicine?

Of course, we should first remember the One Health principle: the first step to good health is a positive relationship with the surrounding environment. Instead of ravaging forests, extracting climate-altering fossil fuels, waging genocidal and toxic wars, polluting air and water, consuming excessively, and abusing mountains and seas with overtourism, perhaps we should start with the health of ecosystems, the foundation of our longevity and wellbeing. Becoming centenarians capable of running on a desertified planet, devoid of biodiversity and with an uninhabitable climate, is not the prospect we want for ourselves, nor for all generations to come.

DOWLOAD AND READ ISSUE #57 OF RENEWABLE MATTER: HUMAN TECH

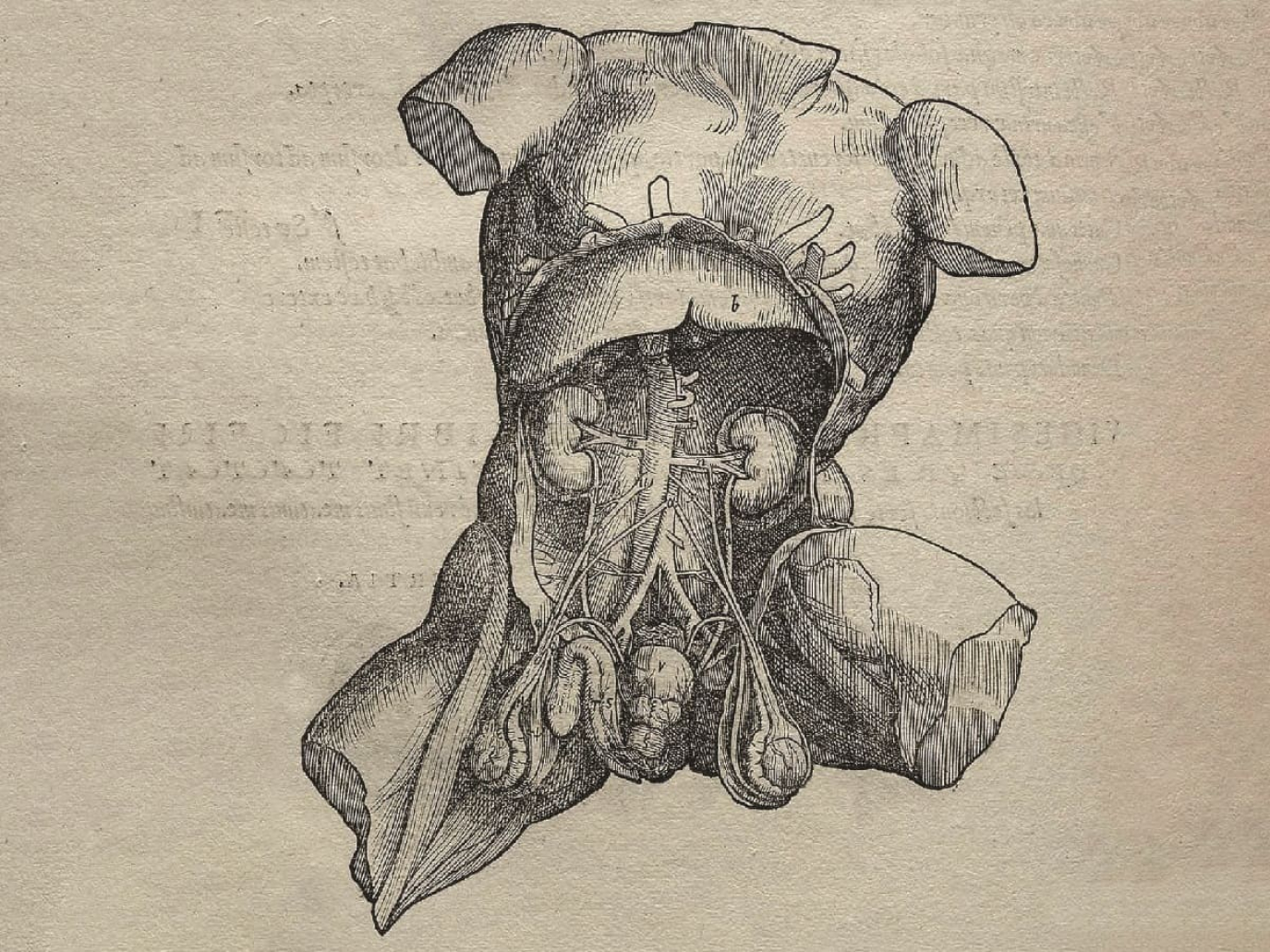

Cover: image from Andreas Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica (1543)