Green corruption is the circular economy’s sworn enemy: its very anthitesis, its tombstone. A liquid enemy that feeds and grows on red tape inefficiencies and awful governance in the management of environmental resources, of the racket, lack of ethics and collective responsibility. An even worse enemy of those lobbies still firmly clung onto fossil fuels.

Everywhere in the world but mainly in countries with institutional and economic fragile or in transition systems, the use of corruption to pillage environmental properties has always been a normal strategy of economic policy. A quick fix to amass money without too many qualms. In particular, in African and Asian countries and in South America, corruption was instrumental in robbing biodiversity to the advantage of rich Western markets: clearing the land, importing toxic waste from industrialized countries in exchange for weapons, as journalist Ilaria Alpi, murdered in Somalia on March 20th 1994 was trying to disclose.

|

|

|

Because of this very corruption series of killings, the CITES Convention, ratified in Washington in 1973 and signed by 182 countries, included over 13,000 species of mammals and birds, thousands of reptiles, amphybians and fish, millions of species of invertebrates and almost 250,000 plants in the list of endangered species.

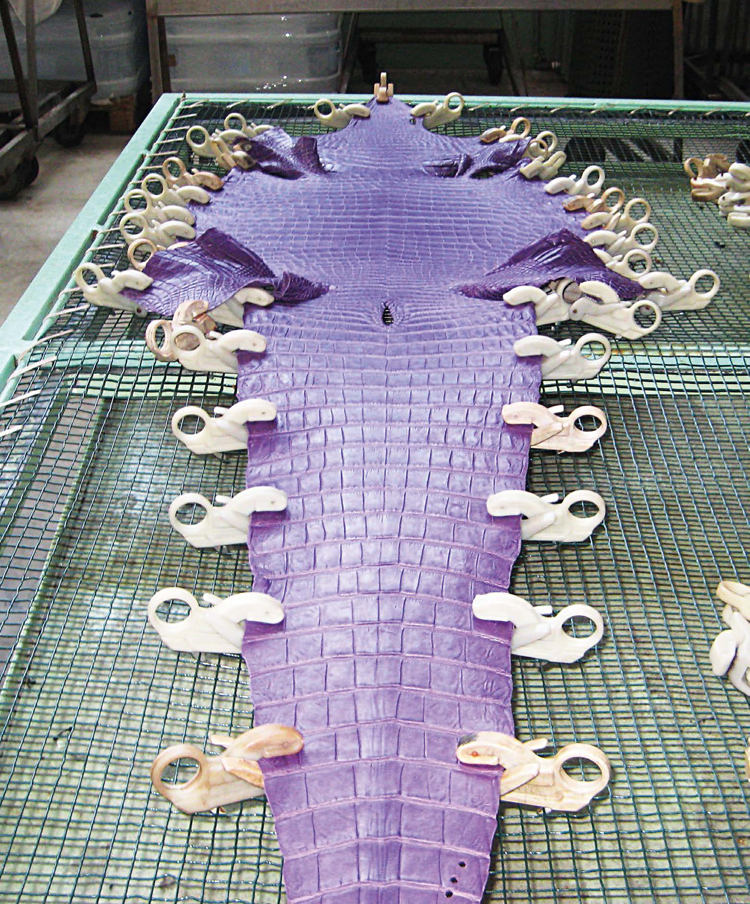

The illegal trade of reptile skins and byproducts has become one of the most deplorable trades, and at the same time one of the most profitable ones thanks to corruption and various criminal systems. According to the UN, it amounts to $8 billion a year and managed to blend in with legal practices, leading one fifth of known species to the brink of extinction so far. The checks on this extraordinary trade tend to revolve around exhibited documents, which more often than not tell a completely different story compared to reality. At international level – between 2008 and 2012 only – the number of traded protected live animals was about 5 million, while 11.2 million skins were exported, with a total of 372 species involved (CFS, 2015), all included in Appendix II of CITES. It is mainly the luxury market of the footwear and clothing industries (crocodile skins and similar, pythons and similar) that feed the demand for the black market. The corruption’s task is to create profit margins between the various international supply chains, pushing up the monetary value of individual animals, from €30 paid to capturers, representing the first link in the supply chain to €50,000 for a single high fashion garment (Progetto Civic, 2016). As CITES’ investigation sources highlight, corruption is fundamental to circumvent checks and amend required certifications, legitimizing criminal networks mainly in the countries where reptiles originate such as Asia, Africa and South America: from captures to treatment, through to skins wharehouses, before they reach European handcraft workshops, mainly Italian and French. The huge economic gap between countries where the skins originate and those where they are sold adds fuel to the fire: a backhander pocketed by supervising authorities in the first phase of the supply chain may be worth a year’s salary.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The timber industry is another key sector in the green corruption, especially fine timber protected by CITES Convention. According to the European Parliament data (2007), 35% of timber imported into the European Union in 2006 came from illegal resources, mainly from Russia, Indonesia and China. And there is more: almost 80% of forest logging in the Amazon is illegal or occurs without permits. Between August and September 2014 Greenpeace used in the Brazilian Amazon forest GPS technology to track the criminal market linked to illegal logging and ensuing timber trade, showing how the timber industry in the State of Parà is in part to blame for this trade since it provides the necessary paperwork to be shipped abroad.

Illegal logging is thus the first step, followed by the passage from sawmills (often complete and utter “washing machines” of illegally-logged timber), transport and trading (direct or through intermediaries). Usually, criminal groups take advantage of corruped élites, public officials and salaried police officers, essential pieces in the puzzle of cross-border trafficking. In Europe, the Balcan peninsula is one the most exposed areas to illegal timber trafficking through corrupted networks. It is from here, from the Balkan route, that most fine timber is dispatched to the rest of Europe for a variety of uses such as maple used in Italy to make the best violins in the world.

The easiness of cirumventing checks, the objective difficulty in certifying authorizing procedures of movements and in actually applying due diligence and compliance mechanisms, and above all the considerable expected benefits, are tangible conditions smoothing the way for green corruption.

The seriousness and spread of corruption in the environmental plunder is further confirmed by the number of people killed due to their commitment to protect natural resources. From 2002 to 2013, 908 people from 35 different countries were murdered; over the last four years, on average two activists a week were killed. But impunity for such crimes is extremely high: only 10 criminals have been captured and punished. The worst hit areas are, from what is known, Latin America and Southeast Asia.

In many countries, NGOs, political movements and ordinary citizens started to take action to try and stop the corruption drift, of course wherever it is possible to demonstrate. One of the most recent cases is Morocco, where, following the arrival of 2,500 tonnes of special waste from Italy, the national association for the fight against corruption in Rabat caused a huge public protest. The same is occuring in Tunisia and randomly in Eastern Europe, in South Africa, Nigeria, Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, Lebanon and Afghanistan.

Link between GDP and Environmental Crimes: The Italian Case

Besides investigative evidence, the strong link between environmental crimes and corruption is demonstrated also by using social sciences. Thanks to the quantitative analysis carried out by economist Filippo Reganati at La Sapienza University, using the Pearson correlation coefficient (adjusted on regional level and for the 2007-2011 period) between the number of environmental crimes – including people reported to the police and arrested – convictions on corruption charges (artt. 318-322 of the Italian Penal Code) and per capita GDP, there is a positive and statistically significant correlation between environmental crimes and convictions on corruption charges, and a symmetrical negative and statistically significant correlation with the regional per capita GDP. This means that ecocrimes and corruption go hand in hand. The Pearson coefficient tells us that the higher the per capita GDP, the lower the rate of proven environmental crimes. From this point of view, environmental crimes appear particularly rampant in the regions with the worst performing economy, where the economy languishes in the old and exhausted patterns triggering a negative spiral with disastrous socio-environmental results.

Alberto Vannucci at Pisa University also came to the same conclusions despite using a different and more qualitative indicator, the Quality of Government by Göteborg University, worked out though a survey with questions on the perception and personal experiences of bribes. In this instance as well, using data from Rapporto Ecomafia 2013, the highest number of environmental crimes and charges took place in those regions with the highest number of convictions on corruption charges.

These results prove that good environmental governance, quality of company’s capital and the adoption of sustainable economic models with a strong link to local areas are the best tool to protect common goods and stop shady characters. Thus, besides defending ecosystems, the circular economy has in its DNA chromosomes to look forward in the right direction, doing away with green corruption.

Globalization has also caused the expansion of the green corruption market. As Marco Arnone explains, “The more markets expand and interconnect at global level, the more corruption rises taking advantage of different corporate structures present in different countries and actually hindering the application of criminal law.” According to Arnone, “Market globalization has also highlighted the fact that some countries are more prone than others to ‘export’ corruption. Some multinationals are indeed more prone than others to corrupt public officials of the country where they operate, thus ‘exporting’ corruption.” Indeed, there is a positive correlation between the level of domestic corruption and the level of corruption exported by single countries: where corruption is rampant, businesspeople have a tendency to export this kind of corporate culture to the rest of the world.

Economic and environmental costs are huge. In Italy alone, between 2001 and 2011 10 billion would have been lost due to environmental corruption (Data by Legambiente, Libera and Avviso Pubblico, 2012). In Italy in the last six years, Legambiente has registered 302 enquires of great national importance leading to 2,666 people being arrested, 2776 being reported and involving 68 national public prosecutor’s offices (Ecomafia 2016, Edizioni Ambiente, Milan 2016).

|

|

|

Green corruption is basically the tool used to domesticate and circumvent laws and regulations, finding the perfect habitat especially in the meanders of the linear economy by exacerbating the classic mechanism of privatizing profit and socializing both environmental and social costs. It is based on the strength of the homo oeconomicus dogma praised to the skies by neoclassical theories, the extremely utilitarian actor, rational and amoral steering the economic enterprise towards the maximization of its own objectives without worrying about the disasters it leaves behind (Karl Polanyi, 1944). By definition, corruption is indeed a rational crime (Gary Becker, 1968). If the economic enterprise is freed from social and ethical considerations and pursues only economic usefulness, it is very likely the environment and common goods will be the first to fall under the axe of cynical and rational market rules and criminal intermediation. The Tragedy of Commons, as Garrett Hardin warned back in the 1960s.

Moreover, the corruptive currency is particularly effective amongst the recesses of environmental rules based on the “command and control” paradigm setting the minimum environmental standards (that is, accepted polluting levels) that everybody must respect – and that above all those running a business – but controlled by a technical-bureaucratic apparatus at various geographical levels where subjective discretionary power margins and procedure inefficiencies provide a fertile soil for illegal markets and patronage systems to thrive. The stricter the environmental regulations are, the higher the price of corruption becomes. It is no coincidence that there is plenty of economic literature identifying amongst the conditions favouring resorting to corruption high fiscal pressure, excessive regulation of legal markets and bureaucratic regulation in general and high public expenditure (Centorrino, 2010).

CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, www.cites.org/eng

Top image: vector design by Gan Khoon Lay - The Noun Project