Walking around Taipei, Taiwan, one seldom sees trash or even trash cans. Instead you might see people washing plastic bottles, carefully sorting computer parts and families waiting for the nightly garbage trucks with blue trash bags.

This trash transformation is a recent phenomenon. In 1993, Taiwan had a trash collection rate of just 70%. Meaning that 30% of waste entered the environment either through littering or burning.

Over a ten-year period, Taipei has not only increased its recycling rate to the point where it is now considered one of the top five cities for recycling, it has also substantially reduced waste production. How have they achieved this? Through waste charging schemes and urban recycling projects funded with a garbage levy.

Pay-As-You-Throw

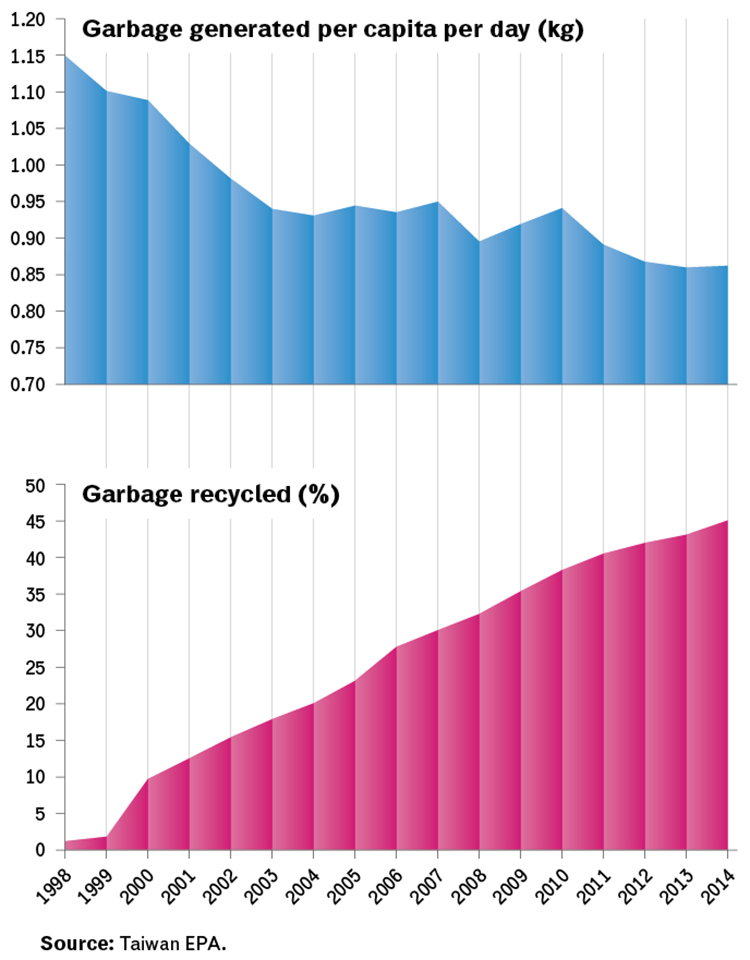

Pay-As-You-Throw (PAYT) schemes were introduced simultaneously with public education programmes. Together, these strategies decreased waste production from 1.08 kg of waste per person per day in 2001, to 0.86 kg per person per day, almost eliminating the need for landfills.

Charging for waste disposal, typically called a “pay-as-you-throw” scheme (PAYT) reduces total waste output by citizens and industry by creating a financial penalty for garbage production. In 1991, Taipei City experimented with waste fees by charging residents for water, assuming that if residents used more water they also created more waste. Failing to reduce waste, Taipei then decided to start charging for waste by volume in 2000.

When the programme first launched, citizens attempted to circumvent the measures by disposing of their waste in public trash cans. This resulted in fines, removal of public trash cans and educational programmes to educate the population on proper waste management. Shortly after launching the programme, residents complained that they had to dispose of too much food waste, raising the costs substantially. The city quickly responded with a food waste composting system in 2003 that allowed residents to dispose of organic waste freely. This policy came six years before San Francisco’s acclaimed food waste composting law, yet few outside of Taiwan know of this achievement.

Later, the city implemented a blue bag programme where residents had to purchase trash bags with a built in disposal fee. Recyclable items have no extra charge, thereby encouraging re-use. Since the launch of PAYT, per capita waste generation in Taipei fell 31% in 15 years, from 1.26 kg per person per day in 1997 to 0.87 kg in 2015.

Furthermore, the financial penalty scheme has driven recycling, increasing recycling rates from 2% to 57%. While Taipei adopted the scheme first, a similar trend is emerging across Taiwan. Taipei city boasts a 56% recycling rate, the highest in Taiwan, thanks to the PAYT and EPR schemes.

Wrapping Up

Today, Taiwan incinerates less than it did in 2000, despite a peak in 2007. In fact, many incinerators around the island operate well below capacity. Landfill use, which was once threatening to take over the island, has decreased by 98%. Today, Taiwan produces more recyclable waste than unusable waste and has made considerable progress towards a “zero waste society.”

Now Taipei City has passed legislation to fully ban single-use plastic bags, and straws. The solution for bags? Simple: require stores to hand out city approved trash bags and citizens who forget a reusable bag are charged for a trash bag which they can then re-use to dispose of their non-recyclable waste.

Taken as a whole there is a clear lesson to be learnt: charging for waste disposal and developing an EPR scheme drives down waste production, builds infrastructure and increases recycling. The result is that Taiwan has created a multi-billion-dollar recycling industry by cleaning up it’s streets.

Taiwan has shown us that, when faced with rising waste, there is the potential for developing successful waste management policy.