COP30 comes to an end as a mirror of the current times. Multilateral cooperation on climate change barely survives, notwithstanding geopolitical tensions. Growing are the divisions between countries that do not want to give in on the long-term phase-out of fossil fuels (the Gulf countries, Russia and the US, which were absent), those with ambitions to accelerate the Paris Agreement and those willing to sign anything to preserve the COP and bide their time for a better global political climate. The worst COP since Madrid, and perhaps even since Copenhagen.

The Mutirão Decision, the final political draft of COP30, dull and flat, does not explicitly mention fossil fuels and fails to respond to the appeal by President Lula and over eighty countries for a roadmap on fossil fuels and deforestation. It merely reiterates the trajectory outlined in Dubai on this issue, the “transitioning away” from coal, oil and gas, to be achieved somehow by 2050. To support this transition, the COP points to a new series of processes to accelerate the energy transition, such as the Global Implementation Accelerator and the Belém Mission to 1.5, which hopefully will become practical tools enabling countries to collaborate, each with their own paths, to advance in defining “how” to move away from fossil fuels.

A few are attempting to respond, especially Latin American countries: rather than waiting for the next COP, Colombia has offered to host, in collaboration with the Netherlands, the first international conference on Just Transition Away from Fossil Fuels, from 28 to 29 April 2026 in Santa Marta, on the northern coast of Colombia. The aim is to create shared strategies among the more than eighty signatories of the roadmap for phasing out fossil fuels. However, these are all initiatives that still need to be established: a roadmap on fossil fuels, approved at COP30, could have defined a plan for all 196 countries with dates and targets, sending a clear signal to the financial markets and the oil and gas industries.

Ten years since the Paris Agreement

A grim tenth anniversary for the Paris Agreement. Instead of celebrations, there is a race to salvage what can be saved, leaving negotiators, civil society and journalists perplexed and sparking heated protests in the final plenary session. “The barely adequate result achieved in the final hours of COP30 keeps the Paris Agreement alive, but highlights the resounding failure of developed countries to meet their commitments under that agreement,” commented Rachel Cleetus of the Union of Concerned Scientists in an email. A blame that does not fall solely on the US and Europe this time: the process was blocked by the unyielding Gulf countries, Russia, and even China, which failed to show global leadership on the transition in Brazil.

Italy played defence, refraining even from following the United Kingdom and Germany in the eighty-country bloc in favour of a structured roadmap for phasing out fossil fuels. Instead, Italy simply reiterated the resources allocated (up from previous years) that will largely support the Mattei Plan. Closer to Saudi Arabia and Hungary than to the United Kingdom and Colombia.

The Brazilian presidency, led by André Correa Do Lago, attempted in every way to achieve a significant result, but had to capitulate on fossil fuels and forests, despite the launch of the Tropical Forest Forever Facility. The result pursued was overly ambitious, in a location that made everything more difficult, without working in advance with those who would be the natural adversaries of this path: the Arab states.

Civil society almost unanimously sided with putting the negotiation process under scrutiny, increasingly calling for real reform, starting with COP31. As Andreas Sieber, associate director of policy and campaigns at 350.org, explains: “Belém did not falter. President Lula and Minister Marina Silva have shown leadership in addressing the issue of fossil fuels. But the presidency’s negotiating team has huddled behind closed doors, stifling the multilateral spirit needed for higher ambitions, while wealthy countries have declined to put real financing on the table. Yet the momentum was unmistakable: more than eighty countries called for a roadmap for the transition away from fossil fuels, and the approval of the Just Transition Mechanism showed that multilateralism can still work.”

Finance and adaptation

On the financial front, COP30 sends a more encouraging message about the importance of investing in resilience and agrees to triple the share of funding for adaptation by 2035, which is arguably the most important technical news to come out of this. Pledges to make climate finance more predictable, accessible and commensurate with the needs of vulnerable countries are emerging, essential elements for a more equitable financial system aligned with climate challenges.

“This is not about tripling resources by 2030 as requested by developing countries, but it is a major acknowledgement that adaptation funding must continue to grow as climate impacts increase,” says Eleonora Cogo, head of the finance cluster at ECCO, the Italian climate think tank. “The reference to 1/CMA.6 places this new target within the framework of the NCQG, which means that developed countries take the lead and other countries are encouraged to contribute voluntarily.”

The amount will not be known until 2027, when data on 2025 funding levels will be available. Less satisfaction, however, was expressed regarding the expected adaptation indicators, crucial for the implementation of NAPs, the National Adaptation Plans. Many experts felt that the 60 indicators adopted should have been more detailed to ensure that global progress would be measurable.

The adopted list includes indicators to monitor the means of implementation (financing, technology transfer and capacity building), an indicator on gender-sensitive adaptation policies and suggestions for disaggregation (e.g. by gender, age, geographical areas and ecosystems). Last-minute changes to the list of indicators, however, which had been carefully developed by a group of experts over the past two years, compromised its credibility and will make implementation more difficult.

Trade, CBAM attack spared

There was little mention of it, but one of the most important discussions at COP was on trade. The critical point was the so-called unilateral trade measures, including border carbon adjustments and import regulations linked to deforestation. The European CBAM was under attack, but European negotiators managed to ensure it was removed from every decision (for the time being), defending a mechanism relevant to Western green industry. Countries that view the CBAM as a disadvantage for developing economies were dissatisfied. In the end, it was agreed to hold three dialogues at the subsidiary bodies on strengthening international cooperation in this area: the outcome of these exchanges will be further reported at a high-level event in 2028, in collaboration with the WTO.

COP31

The next climate negotiations will be held in November 2026 in Turkey, with Australia co-chairing on behalf of the Pacific island countries (with a pre-COP to be held in a Pacific nation). Back to a transitional negotiation, without the excessive expectations generated by the Brazilian presidency and the media (the decision to hold it in the Amazon region mobilised the largest number of journalists ever), held in a predictable and easily accessible location.

While COP30 relived the negotiating chaos and disastrous failure of the 2009 Copenhagen summit, COP31 has the cards to start laying the foundations for a renewal of the process, just as happened in 2010 in Cancun, at COP16, where the foundations for the Paris Agreement were laid.

Preparations must be made to be ready for 2030, with a revision of certain rules and a clear idea of how the implementation of the Paris Agreement should be protected and organised. This involves working with the UN Secretariat to create a genuine Security Council for the environment and climate, where countries can continuously discuss implementation. It is not certain that the situation will have improved in a year’s time and that multilateralism will be back on the rise. Action to decarbonise the economy, on the other hand, will continue outside the COP meeting rooms, on an upward curve that shows no sign of stopping, as demonstrated by the countless initiatives that have taken place in Belém over the past two weeks. The cost of climate and natural risks is too high in terms of human lives and the economy to stop this process.

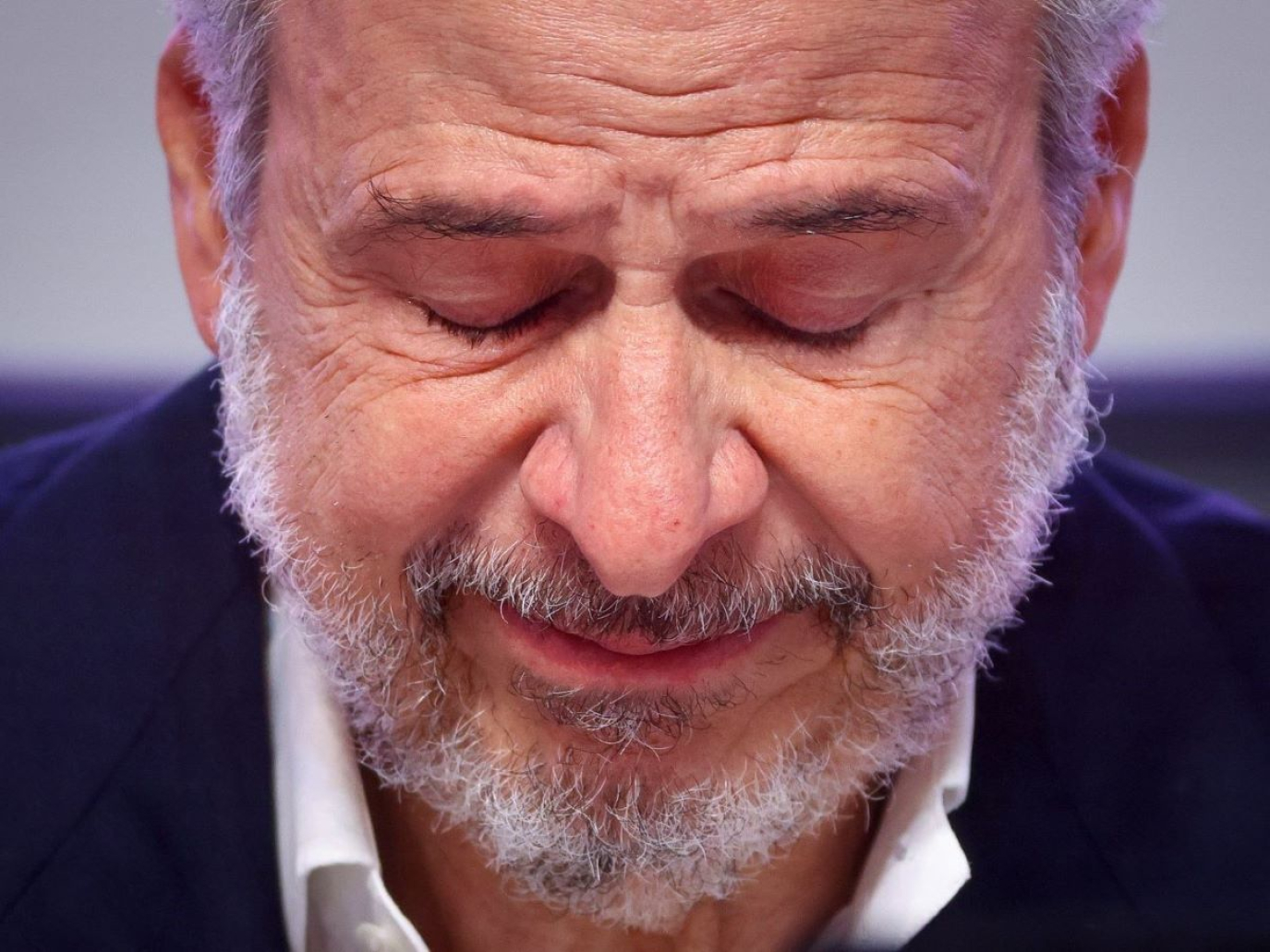

Cover: photo by Ueslei Marcelino/COP30