Thinking circular. It sounds easy but, when dealing with industrial processes, the approach of having a common thread linking products from the cradle to the grave, and considering end-of-life recycling from the very design phase, is not as easy as it sounds. Industrial culture in the 20th century has not adopted this approach and a product’s end of life destiny has long been seen by manufacturers as a non-issue.

Those producing goods do not deal with “waste.” This has been the linear economy mantra, with few notable exceptions embodied in countries that are usually poor in raw materials, such as Italy. Paper, steel, used oils and aluminium are some of the materials Italy has learnt to recycle over the past few decades making a virtue of necessity, and pioneering excellent methods that are profitable and now taken as textbook cases abroad. The Aluminium Packaging Consortium (CiAl) has issued guidelines for the proper planning of aluminium packaging recycling, an unprecedented event at European level, in order “to clarify the reasons behind choices made during the planning phase of aluminium packaging and the management of post-consumer aluminium packaging,” reads the foreword to the document written by CiAl’s General Manager Gino Schiona, who adds: “Therefore, our guidelines are meant to promote greater awareness, amongst the sector’s enterprises, on the impact of products and in particular of packaging.”

In essence, it is an operation designed to inform and educate packaging designers so that their activities take into consideration the end-of-life aspect of packaging and its recycling.

The document opens with a declaration on the importance of the compatibility of packaging with the recycling sector, starting from separate waste collection. For example, the tinfoil used in our homes must be crumpled up before being disposed of in a specific container, otherwise it is excluded from the selection systems. A small yet very important action that guarantees the recyclability of aluminium foil.

The document starts with a description of aluminium alloys and their specific uses, ranging from spray cans to the various series of aluminium, including the 1000 series where aluminium is 99.5% pure; the 8000 series containing iron which, thanks to its malleability, is used for thin sheets, tubs and screw tops; and the 5000 series where magnesium is added to aluminium to make the alloy stronger, for use in can tops and easy-open containers. Therefore, there is not just one aluminium alloy but several ones which have varying quantities of materials according to their various uses. For flexible packaging a 5 to 40 µm thickness is used, for semi-rigid packaging between 30 to 170 µm, and for rigid packaging between 90 to 300 µm. The combination of alloys and thicknesses clearly offer a great variety of possibilities for packaging.

Furthermore, the guidelines regulate the aluminium processing phases, from material primary production which is very energy consuming, and which could be replaced with secondary or recycled materials. This would save a great deal of energy, whereby to produce one kilo of aluminium from recycled material 0.7 kWh are needed, compared to 14 kWh in primary production. This is only considering energy, and disregards the difference between the use of primary raw materials, since the necessary bauxite for primary production contains 54% of alumina, while aluminium from packaging is virtually pure. Because of these economic figures it is no coincidence that worldwide secondary process aluminium accounts for 52% of total production, whereas Italy can boast 100% since 2013.

While on the one hand there is an intrinsic virtuosity in the aluminium production process, on the other there is also excellent commitment to the optimisation of the end product. For example, the traditional 33 cl refreshment can has reduced its aluminium makeup by 30% from 1990 to 2017, going from 16.58 to 11.60 grams. We have also witnessed an improvement in technological production capacity from 1997 to 2014, whereby the thickness of used laminate has been lowered by 37%, whilst maintaining the same quality characteristics.

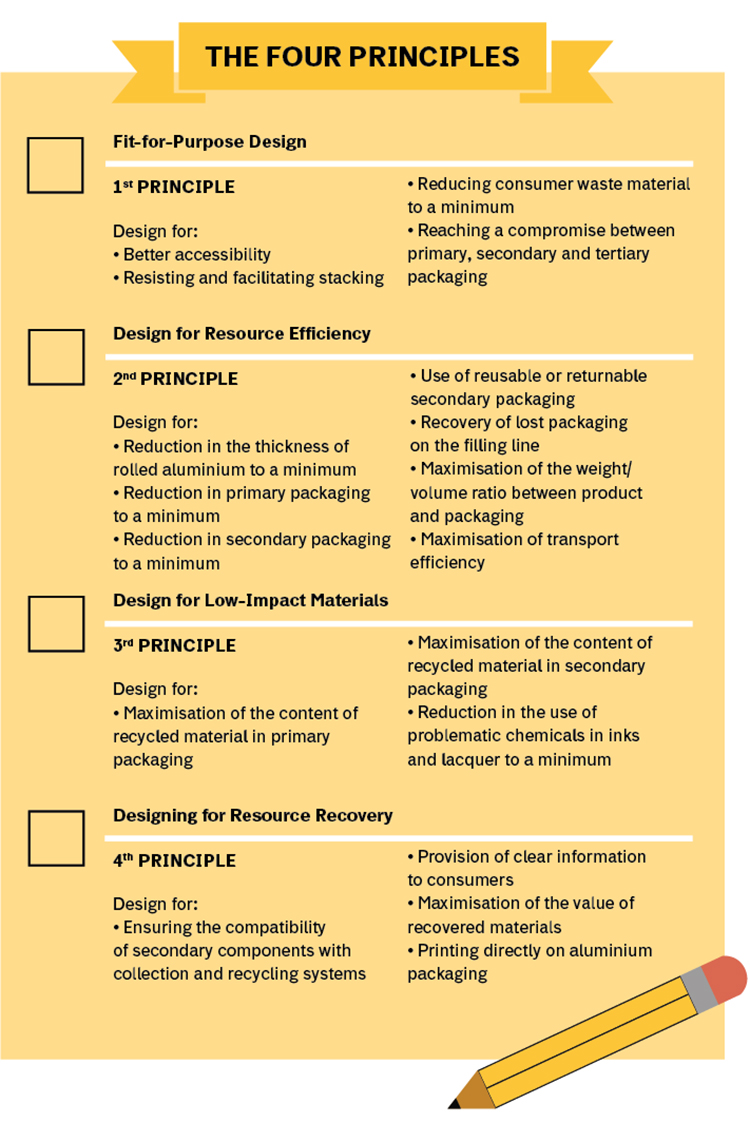

Subsequently, the guidelines give a detailed description of the various aluminium-based packaging types and their respective characteristics, uses, and methods for selection and recycling. The topic of aluminium packaging planning is also tackled. According to CiAl, it must follow four planning criteria: to be useful for their given purpose; focused on resource efficiency; employ low-impact materials; and predisposed for the recovery of resources.

Each criterion has its own practical implementation, both from the manufacturing and recycling points of view, including descriptions of the physics behind their use. For example, in the case of screw top containers where the designer is made aware of the criterion that states the need to reduce the rotational force needed to break initial seals to a necessary minimum. This is because, torque stronger than 1.1 Nm (newton/metre) can create problems for disabled and elderly consumers, as it exceeds their functional abilities. Or, the point where other strategies are recommended compared to the use of cardboard together with aluminium, with the aim of supplying consumers with additional information about the product. Furthermore, compatibility of secondary components with collection and recycling systems is also dealt with thoroughly. This is because rigid plastic components can create problems in aluminium collection and recycling. A practical example of planning aluminium spray cans is also provided via a brief information sheet where all necessary steps required to make such an object are described, taking in strong consideration environmental sustainability.

CIAL, Aluminium Packaging. Guidelines for ecologically sustainable design. Design for recycling.

CiAl, www.cial.it