Italy is a fragile land and it has been increasingly devastated by seismic disasters, which have altered its profile by hitting people and destroying historic villages, settlements, and their artistic heritage. This is especially true today, after the earthquake that hit regions in Central Italy so rich in history and caused severe damage also because public and private buildings were not complying with the strictest seismic codes.

The topics involved are, first of all, those of prevention and of social, cultural, and environmental reconstruction of settlements after the disaster. Not only have the affected areas become heaps of ruins, but also bonds between people, affections, social relationships, and people’s connections with their land were destroyed.

Art has proved a powerful tool to give new life to prostrated towns, involving people, and allowing devastated environments to come back to life with a new spirit. An example is provided by the reconstruction of Gibellina. This Sicilian town, destroyed by a severe earthquake in 1968, became a productive laboratory of ideas, beauty, and sharing, capable of giving a new identity to this annihilated place and activating citizens’ participation through a monumental work of land art by Alberto Burri, a system of disseminated artworks by Schifano, Melotti, and Pomodoro; new buildings by Gregotti, Purini and Quaroni and the Orestiadi theatre festival.

When Emilio Isgrò was the festival’s artistic director, the ruins of the old town destroyed by the earthquake were used as stage wings for the plays (ruins which, a few years later, will be covered by Burri’s Grande Cretto). The town’s citizens, who had returned to places from their old and by then shattered lives, watched the performances and that narrative gave them the strength to start again.

This regenerative process has been analyzed by the philosopher Serenella Iovino in her recent Ecocriticism and Italy. Ecology, Resistance and Liberation. The book retraces the history of some Italian areas (Naples, Venice, Sicily, Campania and Abruzzo – with respect to their earthquakes – and Piedmont) by means of those bodies and natural and artificial objects which constitute them and that provide us with an original interpretation of the country’s environment and culture.

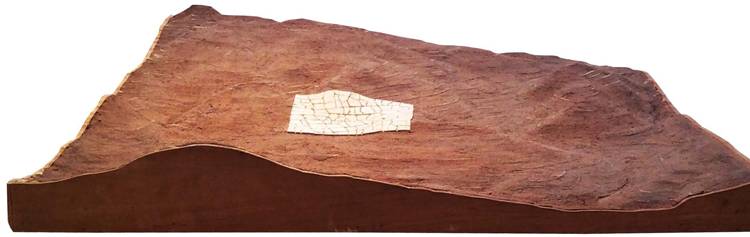

Your books’ cover is dedicated entirely to the installation set up by Alberto Burri in the town of Gibellina (Sicily), which had been obliterated by an earthquake in 1968. It consists of a giant labyrinth of cracks – the Cretto – in white concrete. Why is that photograph so symbolic?

“Burri’s Cretto is the biggest monument ever been dedicated to an earthquake. It covers the old town’s area entirely, since Gibellina was destroyed completely by an earthquake hitting the Valle del Belice in the extremely cold January of 1968. The Cretto’s story is exemplary in many ways. Its quite controversial creation was the result of the will of Gibellina’s mayor, and that is to say Ludovico Corrao, who did not want to resign himself to his town’s disappearance. Thus, on a silent, abandoned hill, covered by a layer of white concrete which follows the town’s layout, the Cretto captures old Gibellina’s last scream and tells us about a place trying to keep on existing as a landscape despite destruction. In its minimalism – which is absurd and necessary, given the installation’s size – the Cretto symbolizes the wound the earthquake inflicted on those places’ body, but also the will to turn wounds into signs, thus transforming them into stories which are necessary to move on. Of course, telling these stories is not easy, especially when there are still open wounds, such as Italy’s earthquakes in 2016. Nevertheless, without a transition from pain to stories, there will be no possible way to both territories’ reconstruction and places’ imagination.”

What were the urban and social consequences of this disaster?

“The consequences were apocalyptic. Here, I am referring to apocalypse as intended by Ernesto De Martino in his book La fine del mondo (“The End of the World”), and that is to say people losing their ‘horizon of mundane operability’ and seeing their own places disappear, along with their past and their material, emotional, and narrative points of reference. A large number of cities in the Belice Valley were destroyed and some of them were rebuilt many kilometres away from their original sites, thus creating both a cognitive and emotional rift within their inhabitants. In addition, as it is the case for every earthquake, destruction was often magnified by inadequate building construction which, more often than not, went along with property speculation. In the Belice Valley’s case, the lack of a connection between town planning and economic development was a serious mistake. Indeed, instead of rebuilding settled areas, infrastructure construction was privileged, for instance that of big motorways which were oversized for those territories, but certainly more profitable for those who wanted to make money. Nevertheless, in this apocalypse, some great social unrest was sparked off. I am referring, here, to the uniting power of Danilo Dolci and Lorenzo Barbera, who had already been active years before the earthquake in claiming farmers’ right against the excessive power of large landed estates and large-scale land ownership, not to mention the Mafia’s. There was a time when the presence of their organizations, i.e. Dolci’s Centre of Studies for Full Employment and Barbera’s Centre for Social and Economic Research in Southern Italy, triggered a great boost in solidarity. A glowing account of this situation is found in Carola Susani’s autobiographic book L’infanzia è un terremoto (“Childhood is an Earthquake”), where the story is told of a family moving from Northern Italy to Partanna’s shantytown in order to support Dolci’s work. Despite all the contradictions of reconstruction, such experiences of solidarity were important for the social and historical survival of those places. If development was marginalized by the Italian State, today, such experiences come back to life through the local community’s effort to take care of more a participative development.”

Over the years, thanks to an unprecedented mobilization of artists and intellectuals (from Sciascia to Beuys and Cage), Gibellina has been turned into an open-air museum of modern art and into a laboratory of art and architecture, disseminated all over the area. Why are you defining this as a path to reconstruction, combining memory and design?

“Earthquakes always cause dramatic breaches. The horizon of meaning of a lifetime is wiped out and, along with it, one loses their habits, places, and landscapes. Gibellina’s example is eloquent: the new town of Gibellina Nuova was built various kilometres away from the old one and, apart from the name, they do not share almost anything. Somehow, it reminds me of the city of Maurilia, in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. As in that story, here, it seems that we are facing different cities that ‘follow one another on the same site and under the same name, born and dying without knowing one another, without communication among themselves.’ However, Gibellina Nuova is not a separate case, because it tried to come back to life through the only possible artistic means – namely contemporary art. Corrao’s challenge lies in the belief that the only way Gibellina could resume its story was that of providing the town with another language. Undoubtedly, this feat was difficult. In order to realize how ambivalent this operation was, it suffices to read Vincenzo Consolo’s words, describing Gibellina Nuova as the ‘emptiness fair’ and the ‘metaphysical city.’ Yet, Corrao thought, as well as the artists who followed him did, that living in a city of art could generate the power to create identity – especially for Gibellina’s youth – and, over the years, the Cretto has also become a substantial part of the city’s evolutionary identity. It is not always easy to adapt to the changes of language which cross landscape, especially if it is a domestic landscape such as that of a provincial town. There is still an open challenge for the Italian State, namely that of not turning Gibellina Nuova into an archaeological site of the present era by leaving the town to its fate. Cities of art need their State to become aware of them before they crumble. Funds and actual political attention are necessary to such particular and significant situations. Gibellina risks falling apart before it has become integral part of contemporary Italy’s fabric and, in this case, the blame should not be put on another earthquake but merely on indifference.\"

|

|

Photo by Giorgio Redaelli

|

What tools allow the rebirth of a territory hit by a natural disaster to become an experiment reorganizing a community’s social and cultural life?

“The recent earthquakes in Central Italy made those places’ inhabitants endure terrible ordeals. In addition to casualties, an equally irretrievable loss is that of heritage, which marks a temporal continuity between the voices following one another in those territories. Past earthquakes’ stories teach us that there are more ways to go through apocalypse. We have Belice Valley’s case – where many sites were rebuilt in different places and ways – Friuli Venezia Giulia’s – which privileged the method ‘where it was, how it was’ – and then Irpinia’s disaster and L’Aquila’s outrageous ruins, which are still there after almost eight years. It is not easy for a community and a territory to come back to life, but, in order to make that happen, the will is needed to turn wounds into a story. This can mean an often painful change in the language through which one describes their own reality. It is necessary to save whatever can be saved, but also to know how to design change, if the latter is an evolutionary choice and a survival strategy.”