Trading in second-hand goods is one of the world’s oldest professions, but the ecological value of reuse has only recently been recognised. The circular economy package provides tools and targets that increasingly help introduce reuse – and preparation for reuse – in waste prevention and management policies. The second-hand market will be inundated by huge supplies of never previously available goods. The EU and national institutions will have to make decisions that will dramatically change the whole industry. A very hard task ahead if there is no clear view of reality. The European Union demands the “creation and support of reuse networks”: But what exactly needs supporting? Who must be involved in such networks? Today, in Europe, the second-hand industry is made up of a host of activities, sales and trades: peddlers, junk shop owners, flagship and third-party retailers, used clothes or other durables collectors, wholesalers, charity shops and online platforms. Second-hand goods which often travel from richer to poorer areas. Wherever there is higher income, large availability of used goods and limited demand cause low prices. Wherever income is lower, the exact opposite happens and so, by osmosis, there is a constant import/export flow both within and outside of the European Union. Oftentimes, as shown by the Eurotranswaste (2012) and “Holes in the Circular Economy” (2019) studies, such phenomenon cause illegal activities. So much so that in Italy organised crime tends to get a hold of used clothes collected in Municipalities only to use them in international waste trafficking.

General figures reported are contradictory and policy makers risk becoming confused. Available reports sometimes reveal only reuse activities already included in prevention programmes: according to such an approach, Flanders (Belgium) is top of the list, nearing 5 kg per head of reuse, whereas Italy shows negligible results. However, according to the 2018 National Report on Reuse by Occhio del Riciclone and Utilitalia, if all activities that independently carry out waste prevention were included in the count, Italy would probably boast 8 kg of reuse per citizen.

Second-Hand Clothes Supply Chains: The Shape of Things to Come

Collection and recovery supply chains for second-hand clothes are particularly interesting. They tend to anticipate by a number of years structuring and integrating tendencies in environmental policies currently occurring with other durable goods. Most European second-hand clothes are collected with kerbside containers and very often within textile separate waste collection services entrusted by contract code to public procurement contracts. Entrustment is an increasingly important link because it creates complex supply chains that can be summarised in the following main steps: separate waste collection, first stocking in reserve plants (R13), so-called “original” material sale and transfer to recovery plants (R3), treatment/preparation for reuse, intermediate and final sale of the reusable fraction through second-hand channels, recycling of non-reusable fractions, and disposal of what cannot be recovered. Along the supply chain, there are a variety of operators with different targets (some for-profit others non-profit) that operate in one or more steps according to their skills, operational capacity and location in an increasingly international market.

A study carried out in 2016 by Humana People to People Italy and Target Consulting, on a sample of 1,000 individuals, highlights how citizens, besides asking for transparency and rigour in supply chains, are more likely – 84% of the interviewees – to allocate their own used clothes to supply chains promoting solidarity. Environmental achievements are therefore strictly linked to honouring the “solidarity mandate” of donors.

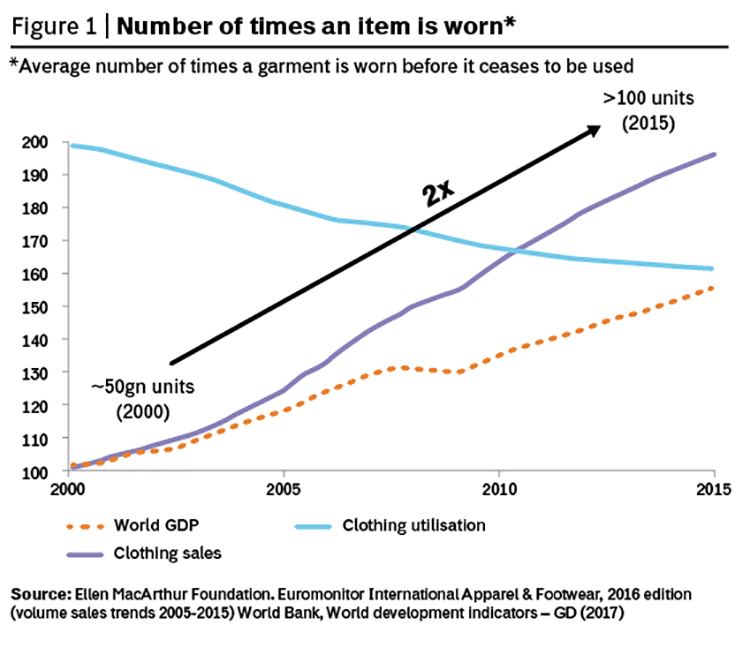

The economic sustainability of services are also worth monitoring. Indeed, unlike other waste fractions for goods, whose collection and treatment constitutes a cost for the community, historically the textile fraction has been conveyed through recovery channels able to produce economic returns that can repay collection costs and sometimes even generate profit. However, the sustainability picture of supply chains is changing. Markets are experiencing a dramatic drop in international sale prices of the “original” (on average 20-25% less compared to 2014) as a result of a number of factors. These include: an overall increase in supply of second-hand clothes due to higher interception in Europe and the US, and to the fact that China and South Korea have recently started collecting and marketing their own second-hand clothes (550 thousand tonnes in 2017; UN Comtrade); poor profitability of selection plants and their difficulty in channelling lower-quality textile waste; and international politics (importing countries that are now ravaged by civil wars or high import tax). Moreover, there is a higher residue to be disposed of at a higher cost per kilo. General lowering of collection quality depends on the fast-fashion boom and change in consumer habits in so-called advanced economies. According to McKinsey & Co, the average consumer buys 60% more clothes compared to 2000 and keeps them for half the time (figure 1).

Price-Based Bids and Economic Break-Even Points

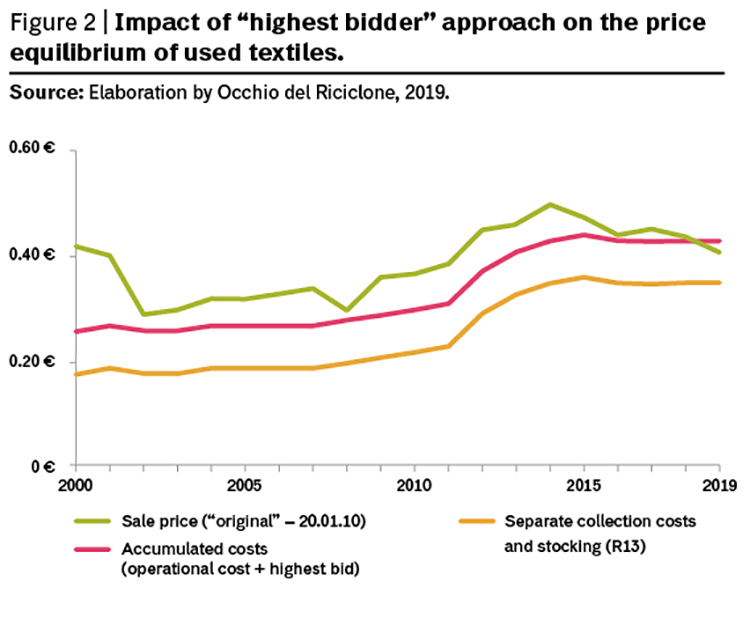

The varying equilibrium between selling price and costs of second-hand clothing supply chains, brings into question the sustainability of entrusting recovery and reuse services (directly or indirectly) exclusively to highest bidder systems. In Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom this is a widespread practice, despite the fact that it is hard to argue that second-hand clothing recovery and reuse are part of “high repetition” or standardisation services, which European Public Procurement contracts allow for. Quality of collected clothes is variable, costs are variable and revenues are not only variable but also subject to radical fluctuations. In 2017, during an event at Ecomondo, Humana People to People Italy highlighted that, during the hardest economic conditions, the presence of a rigid economic factor breaking the sustainability framework risks favouring those willing to slash costs through illegal practices and environmental disregard. In general, highest bidder systems produce ruthless competition amongst operators willing to offer the contracting authority every economic margin in order to win the bid and therefore survive. A rationale that could undermine any action that, in line with the European directive, determines incentives or concessions aimed at making the reuse economy more sustainable (such as Vignaroli, Braga and Muroni bills now being debated in the Italian Parliament). Indeed, such incentives risk evaporating into indirect giveaways to multi-utilities or Municipalities contracting out services. Figure 2 describes – out of a sample of 100 Italian Municipalities – collection cost and revenue fluctuations, highlighting the effects on a break-even point of an integration into costs of a hypothetical bid of €0.08 per kg to a contracting authority (actually contributions exceeding €0.10 are quite common).

Extended Producer Responsibility and Measuring-Oriented Models

Compulsory separate collection of textiles by 2025, introduced by European Directive 851, could generate a global increase of total collection and a decrease in waste that can be turned into energy, making it very difficult to keep up traditional collection programmes based on free service by service providers. The same situation, in the medium term, could be extended to all other fractions of reusable durable goods. Against this background, extended producer responsibility (EPR) could become essential for the reuse system to work. But today more than ever, “brand new” product manufacturers quite rightly see second-hand producers as inconvenient competitors, so much so that if they managed the new EPR schemes they could opt for rationales of reusable grabbing so as to hinder the recirculation of goods. Furthermore, care should be taken when distributing public or producer funds in order to avoid unfair practices or market distortions. In this respect, a word of warning about EPR experiences and public fund schemes for reuse applied in France and Belgium, where there are non-profit groups of second-hand operators that not only benefit from substantial concessions on costs, but also receive up to 75% of their revenue from public or producer funds, focusing their operational processes not on the market but on the measures requested by providers. Getting many incentives allows for setting up prices that competitors (both profit and non profit) cannot match. Sometimes their prices are so low that they attract the interest of foreign second-hand operators that grab goods in subsidised shops only to transport them into their own countries.

Occhio del Riciclone Network, www.occhiodelriciclone.com

Humana People to People Italia, www.humanaitalia.org