– from our partners –

The current financial crisis has inevitably impeached the old mode of economic thought. On the one hand, the failures of the market mechanisms boosted the area of Keynesian economics associated with a strong criticism of distributive inequalities; on the other hand, they also opened the doors to new concepts of scarcity of resources, defence of the natural ecosystems and renewable energy (see, e.g., Agliardi, Spanjers, 2016) to provide potential solutions to the current environmental challenges. One concept that has been developed to resolve some crucial market failures is the circular economy. Then three case studies at firm-level will be presented. They are also interesting because they are related to different industrial sectors and geographical areas.

The cases presented are developed within CESME, a European project on the circular economy in small and medium-sized enterprises, and analyzed in this context thanks to the collaboration with the Department of Economics of the University of Bologna. The research focused on small and medium-sized businesses and this experience has been summarized in an e-book that analyses the cases and the experiences shown below. This is a new attempt to put together university skills, business experiences and a European vision on the circular economy.

One of the instruments for the implementation of the circular economy at the level of industrial processes is the industrial symbiosis and the Eco-Industrial Parks (EIPs). This is probably one of the most promising work directions in the coming years.

Three Case Studies

LoWaste (Local Waste Market for second life products)

In the municipality of Ferrara, the production of urban waste decreased from 102.233 tons in 2010 to 92.678 tons in 2015. Separate waste collection increased from 48.2% (49.305 tons) to 54.35% (50.370 tons) in the same period. Production of pro capita urban waste reduced from 755 kg/ab/year to 696 kg/ab/year.

The LIFE+ LoWaste represent a model of circular economy based on prevention, reuse and recycling of waste using private-public partnership. It was implemented in the municipality of Ferrara together with the cooperation of Hera Group, Impronta Etica, La Città Verde, RREUSE and co-funded by the European Commission through the LIFE+ fund. The project lasted from 11th September 2011 to 30th June 2014. The total project budget was €1.109.000, with €554.500 financed with EU Co-financing.

The objectives of the project were:

- Reduction of urban waste through the development of a local market for recycled or reuse materials promoting a closed local waste management cycle focusing both on the supply side;

- Development of the existing green public procurement schemes in local authorities with a cradle to cradle approach, linking buying procedures to eco-design of goods and products;

- Promotion of waste prevention, encouragement of the recovery of waste and usage of recovered materials in order to preserve natural resources with a focus on life-cycle thinking, eco-design and the development of recycling markets;

- Development of a system for the creation of the Local Waste Market for second life products that can be applied in other local contexts;

- Spreading the knowledge of reused/recycled products to consumers, retailers, producers and public authorities;

- Raise awareness with consumers, retailers, producers and local bodies about the possibility to decrease waste through the reuse or purchase of recycled products.

SQUARe027

SQUARe027 is an innovative fashion luxury brand that, according to its ethic principles, designs and produces an Eco-Friendly and vegan shoes line. Between its strengths, the entirely Made in Italy handmade production. The main goal of this start-up is to provide new products able to satisfy the needs of people concerned about animal wellness and sustainability. To achieve this result, its designer Marco Zanuccoli came up with these shoes that meet these requirements providing at the same time a high quality and trendy product. This firm, founded in 2016 in San Mauro Pascoli (Forlì-Cesena, Emilia Romagna), declares as its mission that it wants “to be able to adapt to the environment and to create something having at the same time a positive impact on the whole ecosystem.” Too many times the environment we live in has been excessively depleted: therefore, as they say, nowadays “a successful firm should act respecting the needs of our planet.”

In order to be such a firm, SQUARe027 applies some of the main principles of circular economy. First, circular economy requires to modify the concept of waste: what once was seen as something to be thrown away, should now be considered as a whole of biological, chemical and material components that must be recovered. Every unit of matter has an intrinsic value that does not disappear as the product which it is part of reaches at the end of life.

Ecopneus

Ecopneus is a non-profit Limited Company for the traceability, collection, treatment and recovery of End of Life Tyres (ELT), set up by the leading tyre manufacturers operating in Italy and based on art. 228 of Legislative Decree 152/2006, which obliges tyres producers and importers to manage a quantity of ELT equal to how much tyres they have introduced on the market the year before.

Ecopneus was born from the cooperation of the most relevant tyres producers and importers in order to permit the right management of ELT on all our national territory, guaranteeing their collection, treatment and recovery. Ecopneus’ founders are very important companies, such as Bridgestone, Continental, Goodyear-Dunlop, Marangoni, Michelin and Pirelli. The procedure for the participation to the initiatives of this company would be enlarged also to other important subject in tyres’ production and import.

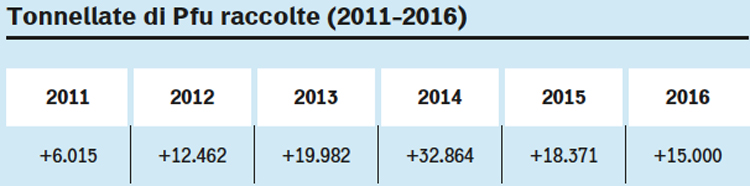

In the past years, Ecopneus collected an amount of ELT higher than law-defined target. Some data (measured in tonnes) are available about that.

In Italy, the production of ELTs amounts to 350,000 tonnes per year (corresponding to 38 million of tyres) and up to now about 20% of them had been collected and sent to specific plants for material recovery. About 50% is destined to energy recovery, while 25% to uncontrolled circuits in order to drop out of the grid.

Eco-Industrial Parks (EIPs): a promising solution... but it needs good chemistry

At face value, the idea of an Eco-Industrial Park (EIPs) is straightforward, as it involves firms in a region cooperating to produce synergies among their operations and match inputs and outputs in order to reduce costs, resource use, waste and emission impacts. This form of “industrial symbiosis” is often compared to an ecosystem in which different species of enterprise share nutrients or pass them down along the food chain. While this is a compelling image, a different analogy is perhaps needed to capture the complexity of this industrial organization. When two or more firms interact, they behave in a manner resembling a chemical reaction: they combine reagents to give a product (e.g. releasing energy or, in the case of companies, generating revenue) and some residue in the form of waste and emissions. A reaction requires some amount of activation energy and, to be considered worth is while, should be exergonic, that is it should release more energy that it took to kick-start it. The reasoning behind EIPs is to find reagents that are highly reactive to one another, that is to locate firms with compatible inputs, outputs and procedures that would allow them to operate jointly in order to generate more products (chiefly revenue, but potentially also knowledge, job positions and other socio-economic goods) than they would if they were to act separately, as well as reduce negative externalities (read: adverse impacts) on the local environment and communities. We’d like to explore the main features of Industrial Symbiosis, and EIPs in particular, outlining the benefits promised by their formations as well as their range of application.

Info

Bibliography

- Agliardi E., Spanjers W., Rethinking the Social Market Economy – A Basic Outline, 2016, RCEA Series 16-01, pp. 1-21

- Boons F., Janssen M., “The Myth of Kalundborg: Social Dilemmas in Stimulating Ecoindustrial Parks,” Van Den Bergh J., Janssen M. (eds.), Economics of Industrial Ecology – Materials, Structural Change, and Spatial Scales, 2004, MIT Press, Cambridge, pp. 235-247.

- Chertow M. R., “Industrial symbiosis: literature and taxonomy,” Annual Review of Energy and Environment, 2(1), 2000, pp. 8-337.

- Ehrenfeld J., Gertler N., “Industrial Ecology in Practice – The Evolution of Interdependence at Kalundborg,” Journal of Industrial Ecology, (1), 1997, pp. 67-79.

- Gertler N., Industrial Ecosystems: Developing Sustainable Industrial Structures, Master’s Thesis, MIT., Cambridge, MA, 1995.

- Hamilton K., “Genuine saving as a sustainability indicator,” Environment Department papers, (77), Environmental economics series, 2000, The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

- Heeres R. et al., “Eco-Industrial Park Initiatives in the USA and the Netherlands,” Journal of Cleaner Production, (12), 2004, pp. 985-995.

- Huggins R., “Inter-Firm Network Policies and Firm Performance: Evaluating the Impact of Initiatives in the United Kingdom,” Research Policy, (30), 2001, pp. 443-458.

- Lei S., Bing Y., “Eco-Industrial Parks from Strategic Niches to Development Mainstream: The Cases of China2, Sustainability, (6), 2014, pp. 6325-6331.

- Lowe E., Creating by-product resource exchanges: Strategies for eco-industrial parks, Journal of Cleaner Production, (1), 1997, pp. 57-65.

- Mirata M., “Experiences from early stages of a national industrial symbiosis programme in the UK: determinants and coordination challenges,” Journal of Cleaner Production, (12), 2004, pp. 967-983.

- Perman R., et al., Natural Resource and Environmental Economics, 3rd ed., 2003, Pearson Education Limited, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow.

- Roberts B.H., “The application of industrial ecology principles and planning guidelines for the development of eco-industrial parks: an Australian case study,” Journal of Cleaner Production, (12), 2004, pp. 997-1010.

- Veiga L., Magrini A., “Eco-industrial park development in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: a tool for sustainable development,” Journal of Cleaner Production, 2008, pp. 653-661.