|

|

Photo by Iwan Baan

|

By its very nature, a city serves as an accelerator of integrated formulas of the circular economy. Citizens’ proximity, production activity, business networks, service suppliers, educational bodies and institutions, create an ideal platform to activate in a short time effective forms of collaboration and business model that complete the picture. The city acts as a hub for the movement of materials and services, offering diversified competences and, at the same time, customers sensitive to new experimentations.

If seen as a tool to attract and reintroduce “nutrients” (whether they are technological, biological or natural), the city encompasses in a concentrated way all the key words of the circular economy: matter, service, network, training, integration.

So, we need to look at the urban scenarios if we want to pinpoint the most innovative solutions for this role to take shape.

By creating the much celebrated Bosco Verticale (“Vertical Forest”), Stefano Boeri put forward a vision of the city where the relation between human activities and the environment takes new forms, succeeding in a synthesis of objectives so far considered incompatible, for example the high population density, the guarantee of a balanced relation between green and built up spaces and the conservation of biodiversity even in the city itself. Following the success of the building in Milan – 2014 International Highrise winner and recognized as the “most beautiful and innovative skyscraper in the world” – a series of tree-lined buildings by other architects in various parts of the world cropped up, and Boeri himself elaborated projects on an urban scale, glorifying the vertical foresting potential as far as the environmental and housing quality and the reduction of soil and energy consumption are concerned.

Renewable Matter reached the Milan-based architect in his study to discuss the role of the city and the planning culture in the transition towards relation models between the environment and society, geared to sustainability.

|

|

Bosco Verticale (Vertical Forest) is intended as a model to build sustainable residential buildings that combine both a housing function and metropolitan reforestation, contributing to the regeneration of the environment and biodiversity while limiting urban sprawl. “A house for trees inhabited by humans,” is how the architect describes it. The first Vertical Forest, built in Milan, is made of two 110 and 76 metre high residential towers: it hosts 900 trees (3, 6 and 9 metre high), as well as over 20,000 plants and a vast range of bushes and flowering plants distributed according to the façade’s position in relation to the sun. If arranged along a horizontal plane it would extend over a 7,000 m2 area.

|

How do you think the culture of those who plan, engineer and administrate cities should change in order for these entities to become real hubs of a new economy? Actually, to turn them into much more, places where the relation amongst human activities, resources and societies is based on something new?

“Today we have to deal with resources that are no longer infinite; they have been depleted or are less and less available, such as soil, raw materials and resources of public investment. That is why social and intellectual resources are fundamental; they have been used inappropriately or even despised, such as cosmopolitan cultures that today live in our ‘city worlds’ or the hundreds of young creative businesses supporting, with no recognition, the economy of our cities.

“But this is not enough: today we have to learn to make the best possible use of synergies and connections between different and apparently distant resources. Unite within one cycle – such as that of nutrition, or knowledge or urban regeneration – production supply chains, processes and energies that stem from different worlds and cover various stages of the production and consumption of goods and services. We should never underestimate the multiplier effect that beauty, aesthetic consistency and the elegance of style have on the economic and commercial value of a product. Beauty is not a stable condition, it cannot be theorized; but we know that in Italy – in the history of design, fashion, cinema, art – on almost every occasion it stemmed from a combination of simplicity and inventiveness. There is no guarantee that beauty will be obtained, but amongst its preliminary conditions, there certainly is that of ‘do more with less.’ Beauty is an added value that when lies over an object it accelerates, as if by contamination, its communication: it is an extraordinary resource rewarding those who are able to discipline their creative talent and offer it to lend limited resources a new life. For example, to a block of marble, a lamp post or a steel tube.”

|

|

Nanchino’s Vertical Forest, which should be completed by 2018, is the third prototype – after Milan and Lausanne – of a project on demineralization and urban forestation that Stefano Boeri Architetti is carrying out all over the world and in particular in other cities in China, including Shijiazhuang, Liuzhou, Guizhou, Shanghai and Chongqing. China’s interest in Vertical Forest and Forest City’s projects is confirmed by the publication, in April, of the book A Forest City, edited by Stefano Boeri Architetti China and published by Tongji University Press.

|

Digital infrastructure has been described as a new determiner in the transformation of cities, after those represented by the creation of energy and transport networks. In your opinion, what is the relation between this digital-based transformation and the establishment of new forms to use space?

“I am thinking of energy. Today the challenge is to make up for the crisis of the traditional centralized model, with the gradual growth of an energy cycle stemming from the widespread presence of thousands of ‘smart networks’ for the production and distribution of clean energy. Using the technologies of digital information to promote information exchange and sharing the energy produced.

“Buildings collecting solar or wind energy are no longer enough. There is a need for buildings that, starting from our most widespread social infrastructure – schools, theatres, museums – also act as energy accumulators and distributors. Buildings that act as micro-power plants, thanks for example to innovations in the use of hydrogen as accumulator and other devices enabling the conservation of locally produced energy.

“It is precisely here, from the transformation of the nature of the last stops of consumption that a new idea of energy is being born. As Jeremy Rifkin suggested, it should phase in buildings able to absorb and conserve more energy that is needed for their needs. So, they must be able to offer and sell some to the nearby people: neighbours, blocks of flats, the district.”

|

|

Taranto Calling is one of the three winning projects of the OpenTaranto competition for ideas whose objective is the regeneration of Taranto’s historical city centre – the Old City – an island between two seas – today lying derelict – despite its extraordinary potential. The idea underpinning the project includes a series of physical and immaterial actions aimed at improving quality of life, configuring an urban welfare system and one of social infrastructure to strengthen the urban community and supplying services for temporary as well as permanent residents. Public space becomes the cornerstone of the transformation, defining more permeability and accessibility, in and outside the island, while building an all-too-often denied relation of continuity with the sea.

|

In your opinion, what is the individual, or individuals, that in such scenario has the best potential to act as a driver for the transformation? Civil society, i.e. people, citizens? Institutions? Businesses?

“’To do more with less’ means that the economic development is not only a variable of financial mechanism and international relations amongst central banks. Relaunching Italy means planning a new relation amongst society, the State and its territories. To understand that the added value that Italy can offer derives from an old attitude to experience every economic process as a local project, to consider entrepreneurial risk a variable of social relations, to pass down to industrial and artisan products the distinctive features of women, men and places where they were made.”

|

|

The new canteen for Amatrice is a project developed thanks to the fundraising campaign “Un aiuto subito, Terremoto Centro Italia,” (“Help now, Earthquake in Central Italy”) promoted by Corriere della Sera, TgLa7, Tim and Starteed. The “Amate Amatrice” (“Love Amatrice”) project represents a challenge both for the tight deadline required and for the budget, exclusively limited to the costs of materials. Thanks to the versatility of buildings, if required, their intended use can be quickly modified, once the city is rebuilt and will need new services. The first construction to be built will be the school canteen, followed by a food court around the open courtyard. The structure will be accessible to the local community and will represent a point of reference for neighbouring villages. From an employment point of view, it will create 130 new jobs.

|

From the Vertical Forest to the Forest City: what role can these projects have in shaping a new “urban bioeconomy”? Was the value of such projects merely a demonstrative one or are they elements of a strategy for a new vision of cities? And in such vision of nature, are green spaces elements of environmental and habitat quality or a vital part of the urban economy?

“The challenge underpinning Vertical Forest and the project of Forest City that we are working on in China is to open up new possibilities in terms of integration between nature and architecture, giving rise to a completely new vision of a city. Buildings become a habitat not just for humans, but also for plants and animals. At the same time, together with the advantages in terms of health and quality of life, they have a direct impact on the urban economy. Trees in an urban context contribute to the lowering of temperature inside buildings between 2 to 5 °C, thus allowing a 30% reduction in air-conditioning and guaranteeing considerable energy savings. Moreover, plants retain water, thus reducing the risk of flooding with all the benefits this entails. A series of actions and factors that make projects such as Vertical Forest tools to recover and optimize energy and water resources.”

|

|

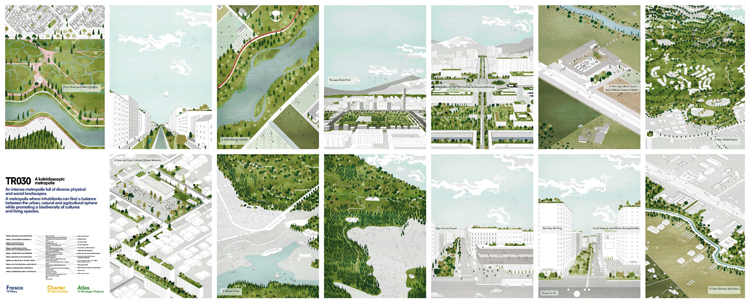

Tirana 030 represents a “vision” for Tirana’s future from now to 2030. On average, Tirana does not display very high buildings, but it is one of Europe’s most densely populated cities, as if it were compressed, sacrifying all open spaces. The strategy aims at leveraging the void in order to create public space, nature and agriculture in order to absorb diversities and complexities within the new urban boudaries. The new public interventions include a continuous forest system around the metropolis; new ecological corridors along rivers, a green ring around greater Tirana as linear public space and a ring road, revamping minor centres as widespread network of interconnected tourist, agricultural and production hubs with access to the urban area.

|

The circular economy represents another challenge for planning. Building involves a high use of resources with ridiculously low levels of “circularity” in many instances (including Italy). In your opinion, what are the main strategies that the planning culture and urban policies can elect to achieve effective results in this field?

“The issue of the circular economy requires a U-turn in the current Italian economic policy. One of the main challenges that urban policies must tackle in the next few years is that of wood, ecological material par excellence and irreplaceable resource for our territory, considering that in Italy the quantity of spontaneous forests keeps on growing due to the abandonment of fields and of Apennine villages. In order to change direction towards a marked reduction of the consumption of resources in the building sector, we need a national plan: a system of wood districts scattered all over the national territory and a supply chain covering the whole wood life cycle and use, from cutting up to recycling and reintroduction into the production cycle. Just as in the last century coal and steel determined a whole production model, now it is time to invest in woods and forests in order to imagine a landscape where forestation, even in cities, becomes an economic model, and not just a social and environmental theme.”

All images: ©Stefano Boeri Architetti