The task is daunting considering the pressing need to provide a growing population of 1.3 billion with a greater standard of living, while income disparities have reached a thirty-year record peak. Resources may simply not suffice and, in certain areas, the environmental carrying capacity is visibly being stretched (air and water pollution). Not surprisingly, the notion of circular economy – which remains strongly rooted in China’s rural practices – appears today as an essential instrument to achieve future quality development. However, in practice, the new effort is driven by the desire to secure resources rather than by environmental concerns.

So until May 2010, when China’s National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Finance unveiled a 5-year plan to develop pilot urban mining facilities in 30 cities, material recycling was a largely spontaneous business that contributed dramatically to rising levels of pollution. The plan aims at modernising “industrial metabolism” to reach, and possibly overtake, the best available international practices. This is best achieved if a few “champion” companies emerge, which is precisely what is happening.

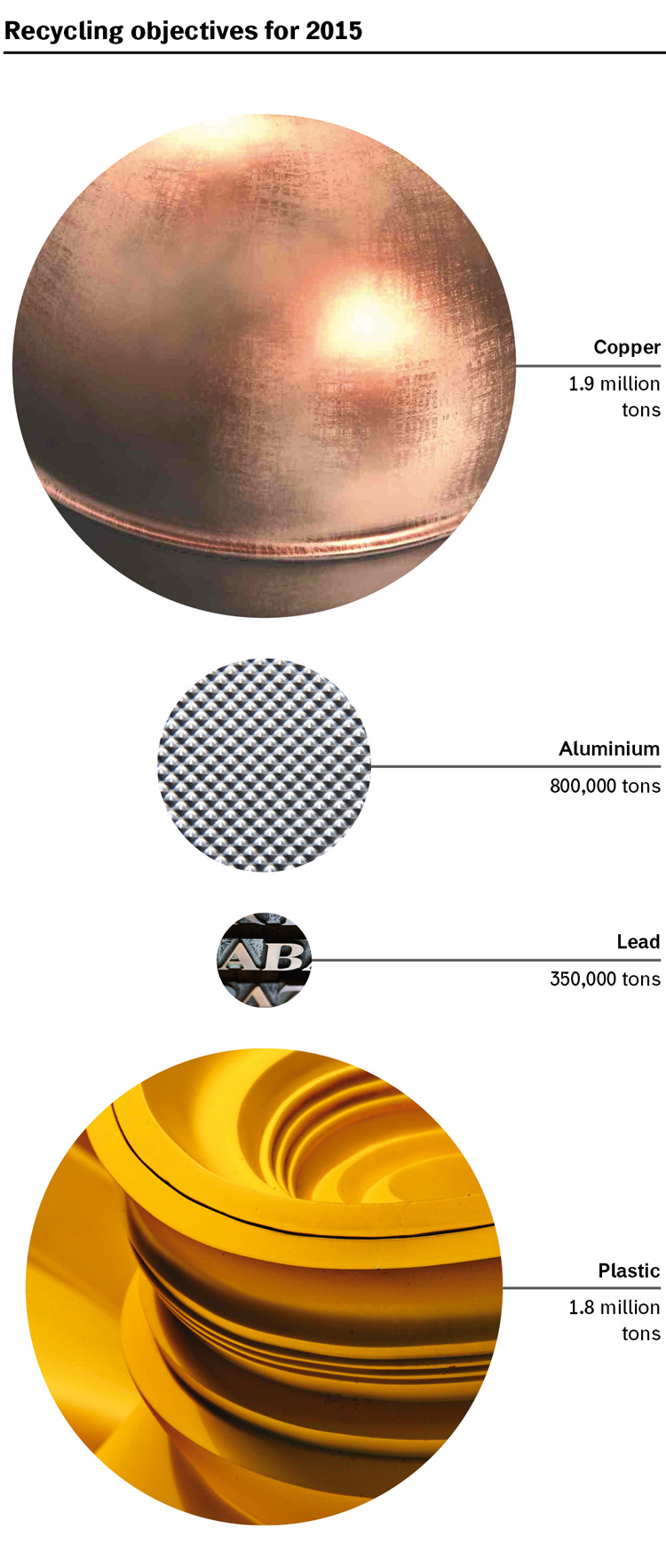

Hence, national and regional governments pooled their resources and teamed up to turn sloppy recycling areas into professionally managed eco/industrial/circular economy parks. At first, efforts were dedicated to 7 major existing sites with the objective of recycling 1.9 million tons of copper, 800,000 tons of aluminium, 350,000 tons of lead, and 1.8 million tons of plastic by 2015. Among these, the Tianying Recycling Economic Park on the outskirts of the city of Jieshou deserves some attention. Described by some sources as one of the ten most polluted cities in the world (the World Bank indicated that 20 out of the 30 most polluted cities are in China), it now harbours over 40 lead processing companies that are progressively substituting the primitive battery recycling and lead smelting technologies that were common until then. According to a 2006 Xinhua News Agency report, unregulated plants in Tianying treated 160,000 tons of lead.

Overall, these efforts are highly appreciated by the media and authorities, although there is much debate among environmental NGOs about how serious and how thorough and effective remediation efforts are. In several cases, the main hurdle is due to increased treatment costs that incentivise the illegal trade for waste battery recovery. A recent report by Chinadialogue.net relayed an interview of Wan Xuejie, deputy president of Jitainli, who explained that his company had spent 200 million yuan on importing and upgrading top of the range equipment from Italy to extract the acid and metals from the batteries. In order to make a profit his company needed to buy batteries at less than 4,000 yuan a tonne while smaller and environmentally damaging companies could pay 7,000 yuan and still make money.

The other six industrial parks, namely the Ziya Circular Economy Industrial Park in Tianjin; the Jintian Industrial Park in Ningbo, Zhejiang; the Miluo Industrial Park in Hunan; the Huaqing Circular Economy Park in Qingyan, Guangdong; the Jinmai Industrial Park in Qingdao; and the Southwest Resource Recycling Industrial Park in Sichuan are faced with similar issues. Meanwhile a further 15 sites are earmarked for phase two of the urban mining initiative.

Altogether, such efforts offer vast opportunities to foster international cooperation. These include technology transfer, as in the case of Italian Merloni Progetti that built a battery recycling plant and seven refrigerator recycling plants, each capable of treating a million fridges/year, for Chinese giant home appliance producer Haier. It also concerns eco-park planning and management as in the case of cooperation between Japan’s Kitakyushu “Eco-town” and its Chinese counterparts in Tianjin and Qingdao, and reaches out to include the development of waste recycling schemes such as those set up by United Kingdom’s Valpak packaging compliance scheme.

An Emerging Champion: China Recycling Development Co

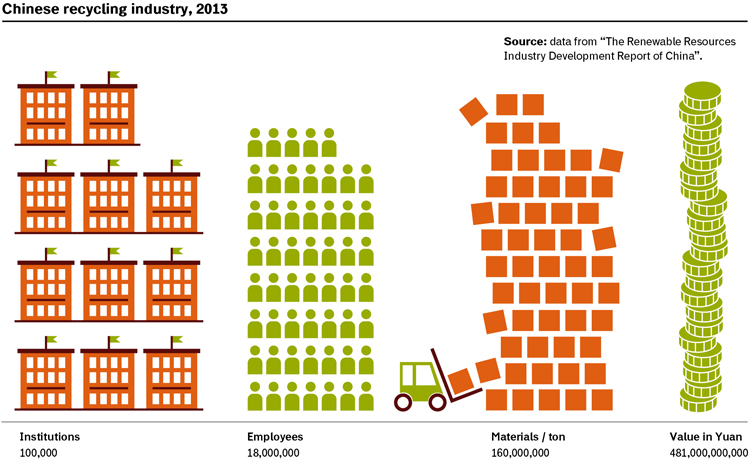

In “The Renewable Resources Industry Development Report of China”, covering events in 2013, China’s National Resources Recycling Association indicates that “there are over 100,000 institutions with 18 million employees involved in the recycling industry (...) and account for 160 million tons of material valued CN¥481.7 billion ($77.6 billion)”. Indeed, the Chinese recycling market appears to be crowded with small and medium sized companies; however, a few big players are emerging. Among these, China Recycling Development Co (CRDC) stands out as a leading company. Created in May 1989 with State Council and China Co-ops Group support, the company operates right across the country through more than 50 branches or subsidiaries and about 3,000 recycling stations. Its direct competitors operate in one or a few provinces at the most.

In 2010, CRDC sold more than 4,800,000 tons of recyclable materials and achieved a turnover of 15.8 billion yuan, and making a profit of 2.918 billion yuan. Moreover, CRDC operates five industrial recycling parks, namely:

- the Huaqing Circular Economy Park, which in 2005 was the first renewable resource enterprise in China equipped with wastewater treatment plant;

- the Changzhou Resource Recycling Industry Demonstration Base, which covers over 4 sqkms;

- Shandong Linyi Resource Recycling Industry Base, which claims to be China’s largest household appliances disassembly and recycling plant;

- the Luoyang Resource Recycling Industry Demonstration Base, which, at the moment, can only claim to be the smallest of CRDC’s parks; and,

- the giant Southwest Resource Recycling Industrial Park which already extends over 5 sqkms, and is literally “exploding” to include storehouses and store-grounds over 53 sqkms and a processing area covering just under 27 sqkms.

The latter is impressive on more than one account. Recently, Kenji Someno, a Senior Research Officer at Japan’s Global Environment Bureau at the Ministry of the Environment, visited the Southwest Resource Recycling Industrial Park and gave a vivid description of his experience. As often happens when looking at Chinese affairs, numbers and timing are striking: “(...) Construction at the Sichuan Recycling Park began on October 18, 2009. At the time, Tang Limin, the Communist Party chairman for Neijiang, announced that with this project, ‘We will bid farewell to our history of ill-disciplined development, characterized by high pollution and minimal added value, and move onto the stage of specialized, concentrated, industrial management development’. On March 9, 2011, the Neijiang government and CRDC signed an investment agreement in Beijing for the second phase of the project. The first construction phase was completed on June 5 that year, and the park became officially operational, as 120 companies moved in. Work subsequently began on phase two. (...) Plans required the recycling park in Niupengzi to recycle 1.85 million tons of resources a year from 2 million electrical and electronic devices and 50,000 scrapped automobiles. It is hoped that this should generate sales of 10 billion yuan and profits of 200 million yuan, creating 1.9 billion yuan in tax revenue and jobs for 20,000 people.” Mr. Someno then goes on to describe the benefits stemming from the facility in terms of avoided environmental pollution, employment opportunities and overall improvement of surrounding activities.

Mr. Someno concludes his account by briefly describing how, even in China, the economic structure of recycling is not as clear-cut as policy-makers, entrepreneurs and, ultimately, citizens would like. As much as reaching for a circular economy is necessary on more than one account, the issue of who is going to pay or make money from digging the waste resource still needs to be thoroughly investigated.