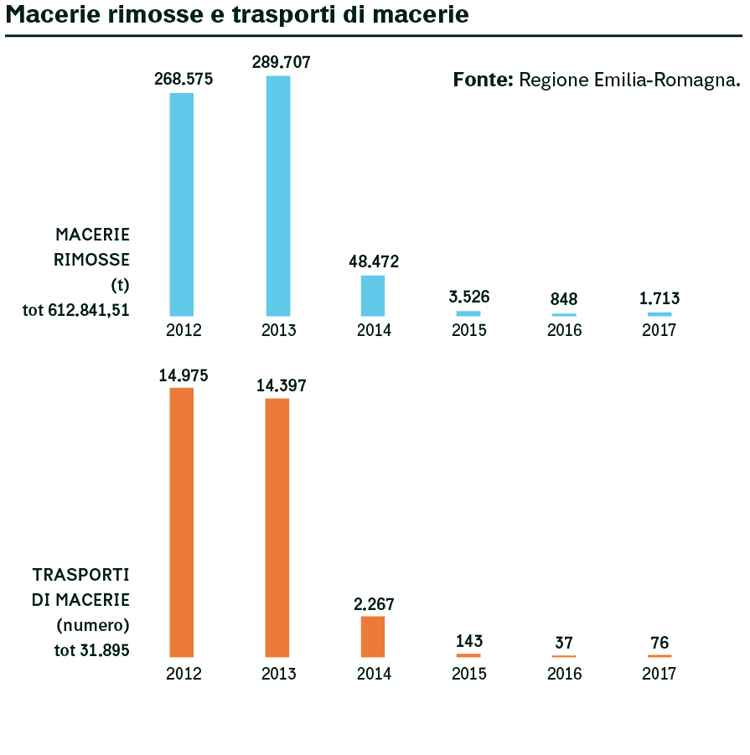

While an increasingly vehement debate is still ongoing over the failure to remove debris and rubble in the Municipalities of Central Italy hit by the quake a little over a year ago, a Region – Emilia-Romagna – proved extremely efficient in managing rubble from the seismic tremors of 20th and 29th May 2012 in an area between the Provinces of Modena and Ferrara. Result (shrouded in an inexplicable media blackout): one year on from the quake, about 70% of rubble had already been removed; a year and a half later from the earthquake, over 90%.

It begs the question of why – as far as we know as we go to press – in the more recent 2016 quake it never occurred to anybody to ask for advice from those who demonstrated the ability to deal with the same emergency so successfully despite the fact that Special Commissioner Vasco Errani oversaw the reconstruction effort both in Emilia-Romagna (up until July 2014) and, for a year, in Central Italy.

True, the circumstances are different: in Central Italy, the municipalities involved are scattered within four regions (Marche, Umbria, Abruzzo and Lazio) and in geomorphologically more complex territories compared to the Po Valley because of, amongst other things, several mountainous bottlenecks. Numbers are also different: in Emilia-Romagna the rubble to be disposed of was a little over 600,000 tonnes, about a quarter of the estimated two million tonnes in the 2016 quake. Nevertheless, the doubt remains as to whether it is not worth resorting to something more than a couple of perfunctory and fortuitous contacts in order to establish what to transfer to Central Italy of the innovative Emilia-Romagna know-how. It should be borne in mind that everything was devised from scratch, following an earthquake hitting houses, private and public facilities, churches and monuments, affecting a production area with a high concentration of premium companies in the biomedical, precision mechanics and agri-food industries which people avoided to relocate from the very beginning. Yet another reason that spurred the local government to swiftly remove rubble to allow reconstruction and start afresh. Suffice it to think that a few hours after the quake the regional experts had already got hold of the aerial snapshots of the affected area. Those images, together with municipalities reports, helped provide an early estimate of the rubble to be removed and to calibrate the extent of the necessary intervention accordingly.

|

|

Bulk handling of rubble in first reception waste facility – Medolla landfill

|

So what are the ingredients of the “Emilia-Romagna model,” praised by the very European Commission that with €15 million co-funded the necessary construction work? “The trump card was teamwork: regions, municipalities, integrated waste management and storage sites services which after protracted debates, sometimes overnight, bonded into a harmonious team where each and everyone contributed,” states Francesca Bellaera – Regional Directorate for the protection of the territory and the environment – who managed the whole intervention together with colleague Simona Biolcati, under the supervision of executive Cristina Govoni. “The Emilia-Romagna Region, in particular, which has supervised the whole operation from day one – continues Bellaera – first of all dealt with the localization of initial facilities situated within the area affected by the earthquake where rubble would be stored; meanwhile it also defined a catchment area for each storage site.” Such task was achieved within about ten days (as testified by the Regional Circular issued on 6th June), “bearing in mind two basic criteria for choosing the facilities: proximity to municipalities and storing capacity,” points out Govoni.

Another winning factor was “naming” ordinary rubble as urban solid waste, a choice that avoided holding the necessary public tenders had waste been classified as special, thus entrusting local integrated service managers with transporting rubble. They, in turn, subcontracted the job to other companies. “In this way, the initial removal of soil rubble or from damaged and unstable buildings to be demolished started as early as June, with an escalation of activities in which the municipalities collected the applications sent in by the owners of buildings,” explains Bellaera. Based on urgency and characteristics, municipalities drew up lists of sites (nicknamed “building sites”) to be removed, which were sent every week to waste disposal managers and to the region.

“Taking into consideration the need to accurately trace movements and quantities of materials from the initial undertaking up to final disposal, an all the more sensitive subject when dealing with waste – highlights Govoni – a shared tool has been created, the so-called ‘dashboard,’ where every haulier, municipality by municipality, building site by building site, recorded the quantity of rubble removed. Such mechanism allowed the Emilia-Romagna region to monitor in real time the post-removal opening and closing of each building site. On average, such operation took three to four days.”

First reception facilities, in turn, weighed the incoming loads, lorry by lorry and reported them to the region that checked figures tallied, without grey areas or discrepancies amongst various sources. But that’s not all: lorries were monitored according to their registration and chassis numbers, load carried and obviously destination. This further stringent checks paid off and allowed highlighting abnormal situations: for instance, thanks to data cross-checking with those owned by law enforcement authorities, means of transports have been detected (used by a sub-contractor outside the region) associated to the registration number belonging to... a Fiat Panda. Investigative bodies are obviously on the case.

|

|

Rubble heap after treatment in fist reception waste facility – Medolla landfill

|

Besides traceability, the other motivation that pushed the Emilia-Romagna Region to devise such strict schemes was the accountability of the allocation of public funds (€4 million at the end of August) and the European ones. The latter, in particular, had to be allocated to companies by the end of December 2013, “such deadline also played a role in speeding up operations,” points out Bellaera.

Adherence to rigourous book-keeping is also faithfully mirrored by the regional report on rubble management, extremely precise and featuring quantities (to two decimal places!) aggregated by municipalities, building sites, waste disposal management, first reception sites, both cross-referred and arranged in single-theme tables. What was the overall outcome of the operations? At the end of August 2017, 613,000 tonnes of asbestos-free rubble were reportedly removed from the 1,595 closed-down building sites out of the 1,774 recorded. 16 are still open, hindered by assets issues.

As to the ensuing reuse of the removed building material, in order to speed up the removal, rubble was loaded onto lorries as it was, without sorting it in situ, since such operation would have required more dedicated means of transport for the selected waste of wood and metal. Therefore, the sorting, was carried out at a later stage within the first reception facilities. The only first-hand selection operated in the building sites involved on the one hand rubble containing or allegedly containing asbestos, for which, as it will be explained below, a specific procedure has been adopted and on the other, historic/artistic artifacts, entrusted with the authorities which, following some inspections, could approve or deny their removal. “After that, once the selection of valuable material to be preserved was carried out, hauliers came back into play and removed the rest,” explains Simona Biolcati.

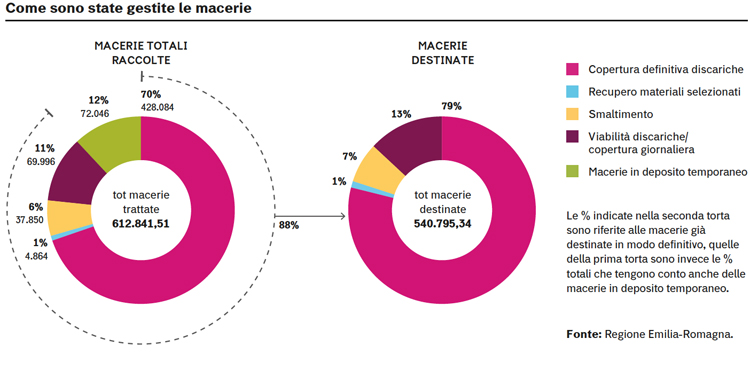

We now come to the final destination of asbestos-free rubble removed and already treated and the reuse of recovered materials. The end-of-August report shows 540,795.34 tonnes (88% of the total removed) allocated permanently, while the remaing 72,046.17 tonnes (amounting to 12%) are still temporarily stored. As to the almost 541,000 tonnes of rubble which “have reached the end of their life” from a management perspective, 93% has already been reutilized.

More specifically, the permanent capping of exhausted landfills where rubble was discarded was the main purpose (for over 79% of the total of removed and allocated rubble); while 13% was used for daily capping and road maintenance within landfills; 1%, represented by selected iron and wood, was sent to facilities for the recovery of such materials; lastly, only the remaining 7% was disposed of. “Unfortunately, due to current regulations it was not possible to reuse rubble, in line with the circular economy, to make new scratches from scratch, such as roads,” comments regretfully Govoni. “Nevertheless, we believe we have achieved quite a result, considering that only 6% was not recovered in any form.”

With regard to the management of rubble containing asbestos, it was agreed that if hauliers only suspected the presence of a tiny trace of the substance they would have suspended loading. Thus, the building site would be temporarily closed and recorded on the “dashboard” as “suspended building site due to alleged presence of asbestos.”

|

|

Loading, collection and soaking of rubble prior to the phase of transport to first reception facility – Building site situated in Rovereto (Novi di Modena)

|

At a later stage, removal would follow, funded by the property owners, according to current ordinary procedures, with some concessions made for timing due to the earthquake. Then, in August 2014, it was decided that the Commissioner would also have dealt with rubble containing asbestos deriving from the earthquake (and not from ordinary reclamation not caused by the earthquake!). Then the building sites that were suspended reopened, while in collaboration with the municipalities a thorough mapping of the remaining sites with asbestos was drawn, 125 in total. So, with a first bid for tender managed by the region the final-destination landfill was identified and with a second, the hauliers. And here a snag occurred that suspended everything for a year: the company owning the Tuscany-based landfill that won with the lowest bid turned out, post audit, in breach of the antimafia regulations. For that reason, the contract was revoked and offered to the second company down the list, at the centre of the eartquake area, that despite having made a higher bid accepted to carry out the job at the same price as the first successful tenderer.

Thus the removal and permanent storage of asbestos rubble resumed at the end of october 2015 and finalised on 29th february 2016.

Curtain.

Info