In your latest book, The Great Transition, you discussed how we are starting our transition out of fossil fuel. Which technology you see trending right now and which have the highest hope of success?

Well, maybe the most exciting thing right now is the growing use of solar energy. Growing by 30% per year worldwide. The principal reason for that is the cost of solar panels has been decreasing, and now you can get cheaper electricity from a solar panel sitting on the roof. So it is an interesting situation because as more and more people put these panels on their rooftops, the market for utility continues to shrink, but it still has to maintain the same infrastructure. So it has to raise electricity prices, and the more it raises prices the more people put panels on their rooftops. So for utilities it’s kind of a death spiral. This story is being replayed in various places around the world. I mean, the idea that China could be getting more electricity from wind farms than from nuclear power is exciting. If you look at a chart, the nuclear growth curve in China is very gradual and steady; the wind energy curve in China is explosive; going straight up and it’s going so fast. This was not really anticipated by very many people. China has a lot of wind, particularly in the north and western parts of the country. And with the high transmission technologies, they can link that wind power with the larger cities: to Beijing for sure, and even to cities in the costal south, like Shanghai.

With the constant growth of wind and solar power, what types of challenges does that pose in terms of materials and technology infrastructure?

One of the challenges with solar energy is what to do at night. That requires batteries to some degree. Batteries being one, and pumped water being another – where at night when you don’t need it you use the energy from the pumped water back up.

Your take on first-generation biofuels is quite strong but many farmers still see them as an interesting opportunity.

The ultimate limitation on the use of biofuels is photosynthesis. Photosynthetic yields are not high, even in the corn belt of the United States – enormously productive land. Let me put it this way. If a farmer in the Midwestern United States is growing corn, and he can put in wind turbines every so hundred meters, he’ll make far more from the wind turbines than from the corn.

|

|

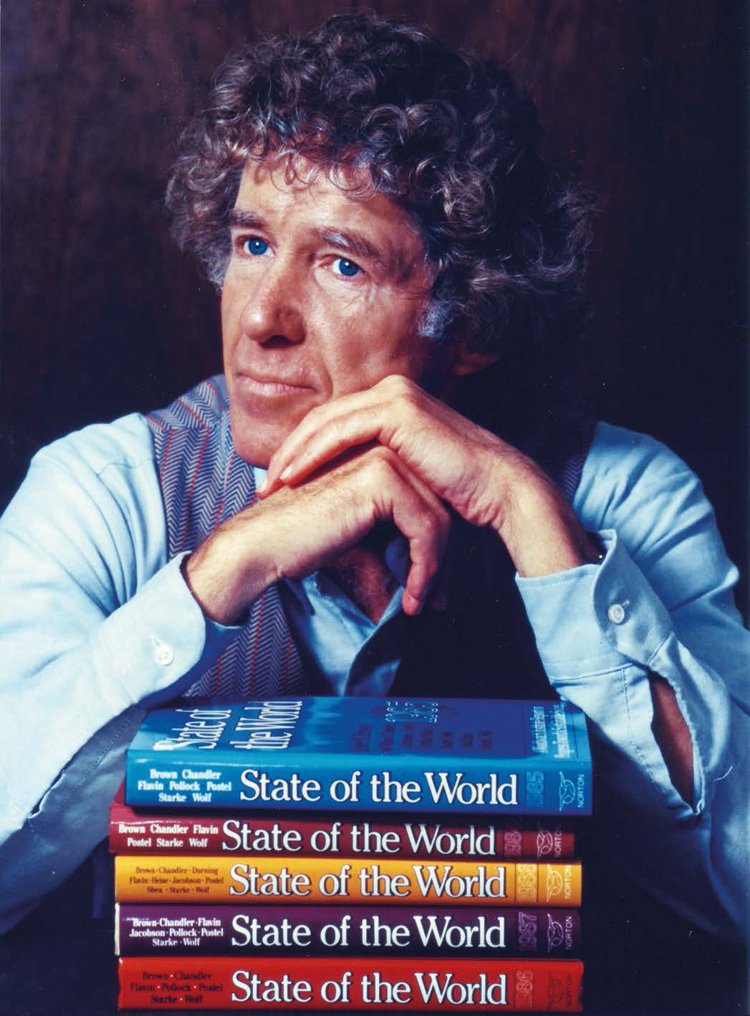

Lester Brown in 1988, with the early editions of the State of the World

|

And it requires a limited amount of soil.

Right. Wind turbines can take up at most 30% of the land, including the location itself and the dirt roads necessary to reach them for maintenance purposes.

So we’re seeing farmers get excited about other sources of income. And for many ranchers, they’re now earning more from wind sales – from royalties – because usually customers buy the wind turbines and then pay royalties to farmers, farmers are earning more from wind royalties than from cattle sales. And there’s growing competition among communities in rural areas in ranch countries to see who gets the wind farm in their area, in their community, because then they get the royalties.

To produce wind turbines, batteries, and solar panels, of course we need more and more materials, and some of them are quite rare – for example lithium for the batteries. We do see something changing in terms of sustainability for the production of these great energy machines. Some think about how to recycle them.

We have very smart technologies in terms of materials. Let me use an extreme example to illustrate what’s happening. 7 bikes in the bike share program reduce the auto population by 1. And the younger generation is not so interested in cars. Let then analyze the material for this green transportation: for a bike it takes about 30 pounds of steel and rubber and so forth; for a car it takes about 2,000 pounds of steel and rubber and so forth. So in terms of materials consumption in a car centered economy, those materials are totally dwarfed in a bicycle-centered economy.

But lots of more complex clean tech still requires large amount of rare materials.

Right. Panels and other devices contain some rare metals, but the exciting thing is that regardless of how much solar or wind energy we use today, it will not affect tomorrow’s availability in any way. And that’s not true with fossil fuels. The more you use, the less there is. The more marginal the remaining resources are, and the more costly.

Furthermore, these material can be reused or recycles. Oil, no.

Things are changing fast. It’s exciting for me as someone who has been working on these issues for half a century, and living through the period when carbon emissions were rising and then the temperature began to rise and you could actually see the early signs of global climate change. But now suddenly we have at least the possibility of halting that or maybe even figuring out ways to lower somewhat the carbon emissions. So this is an exciting period, and this is why I entitled this last book The Great Transition, because the transition is on.

|

|

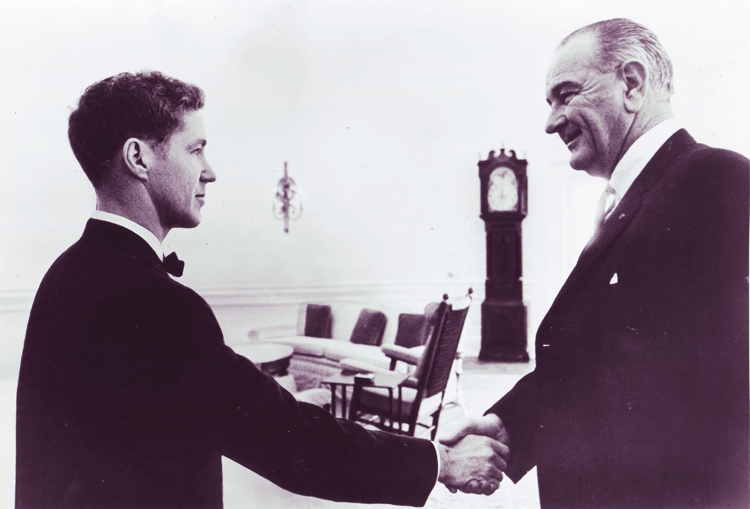

Lester Brown being congratulated by President Lyndon B. Johnson in the Oval Office on receiving the Ten Outstanding Young Men in Federal Service award, 1965

|

More renewables, more circular economy. The world has started to act following a plan B, very similar to Plan B you outlined in your books years ago.

The most interesting signals come from Wall Street. Finance is beginning to vote for green in a major way. And the big investment houses – the big investment banks – are investing in renewables now on a large scale. There are also several billionaires, like Warren Buffett, probably the richest man in the world, that are pouring money in these tech. He put $15 billion into renewable energy in the southwestern United States, and then said “I’m gonna add $15 billion more”. This is billion, not million. Then you have other people like Ted Turner investing in solar power plants. Phil Anschutz, a guy from Denver, he made his billions with coal and oil and is building wind farms in Wyoming now with thousands of megawatts of generating capacity, and is building a transmission line.

One of the points I make at the beginning of the book is that we’re going to see a half-century of change in the next decade.

Do you think that in Paris (at the COP21) there will be any solid agreement on climate change that will actually boost this transition?

I don’t think Paris is going to make much difference. What is happening right now is so strong, and so market driven that the Paris negotiations have almost become irrelevant. It is hard to find a situation where a large group of countries come together and negotiate something: that means very much. But the more people you have at the table the less flexible the group becomes, and so you get these very small, incremental changes, if you’re fortunate. And if the whole thing doesn’t break down as it sometimes does.

Do you think that decreasing oil prices will somehow slow down the transition?

Not very much, because people know that oil supplies are limited. They also know that the prices are going up. One of the examples I have in the book is the Kashagan oil field in the Caspian Sea. The original estimate was they would have natural gas coming out with an investment of $10 billion dollars. Then it grew to $20 billion, then to $30 billion, then $40 billion – and they still don’t have it flowing. If they’d known at the beginning how much it was going to cost, then that coalition of all the world’s leading oil companies wouldn’t have begun. The oil and coal companies are now beginning to see their markets begin to shrink. You look at one of the most dramatic examples: Peabody Coal, which was one of the largest coal companies in the United States. Their stock value has fallen by something like between 70% and 90%, huge. We have this phenomenon that is referred to as stranded assets. You know, at one time oil companies calculated their corporate value not only by the equipment they have and their drilling capacity and storage capacity and all that, but also by how much oil was in the area where they had bought the reserves. And now suddenly, that oil may never be pumped. Those assets are now suddenly not worth that much. It’s been interesting to see how the value of these things has changed. The term stranded assets wasn’t even part of our working vocabulary three years ago, and now suddenly it’s front and center. It includes coalmines that have been closed and will never be opened again. It includes corner service stations for cars. The one near where I live about a mile from here has just closed and is being replaced by a small apartment building because there’s not going to be enough demand for gasoline to support it. In fact, in the United States the number of gasoline services stations we had in 1960 or so was like 150,000, and it’s now down to something like 100,000. The number of service stations will keep shrinking because increasingly we are going to be running our cars on electricity. For a lot of people, the solar panels that produce electricity for the house will also produce electricity for the cars. The idea of having your own automobile fuel on your rooftop 10 feet away is geographically interesting, because it wasn’t long ago that the energy for our cars came from halfway around the world.

|

|

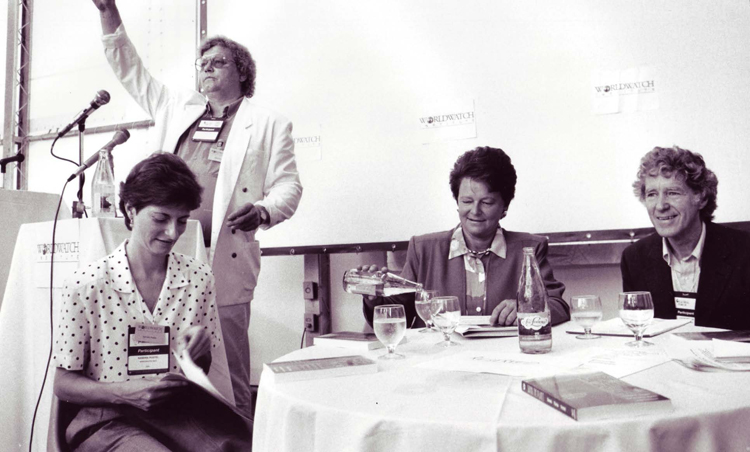

Lester Brown and Gro Harlem Brundtland at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, 1992

|

So we can be positive about energy, and about the future of energy and the climate. But how about food? Many countries have reached their peak productivity.

What we’re seeing on the supply side is that, in the more agriculturally advanced countries, farmers have figured out the things they need to do to raise yields: apply fertilizer, irrigate if necessary, and so forth. They’ve largely done those things now. Once you eliminate the nutrient constraints and the moisture constraints, then it’s photosynthesis that becomes the constraint. If you look at rice yields in Japan, they started rising more than a century ago. Then about 17 years ago they reached a ceiling and flattened out. Japanese farmers have since tried – and they are among the best farmers in the world – but they have not been able to break through that ceiling. The reason is because that’s the amount of photosynthesis that is possible. We saw that first in Japan, and now we’re seeing it with rice in China. Rice yields in China are just 4% below those in Japan. Unless Chinese farmers can figure out a way of taking their rice yields above those in Japan, which I seriously doubt they can, then China – the biggest rice producer in the world – is hitting the ceiling.

The same is happening in Europe with wheat and in the USA with corn.

Therefore, new limits are emerging, which will make things harder for the whole world.

What is the weakest link in our food chain? Water shortages. In India there are now 26 million irrigation wells pumping water at a rate that exceeds the rate of recharge. So in every state in India now the water tables are falling, and in some cases they’ve more or less depleted the aquifers and the wells are starting to go dry.

The same as in California or in the Middle East.

Right. And it’s happening in many other countries. In 50’s farmers started drilling for water and using it to irrigate their crops. Now, and that also true in all of India and a large part of the North China plain, we’re seeing over-pumping of aquifers and the water tables are going down. Now the wells are starting to go dry. Water is emerging as a major constraint on efforts to expand world food production. We’ve got lots of land that would produce food if we could get the water to go with it. Land is not the constraint. Water is. Look at the World Bank several years ago, it looked at India and calculated that 175 million people in India were being supported with grain produced by over-pumping, which by definition is not sustainable over the long term. So we have these huge deficits developing in India in particular, but also in a large part of China and the Arab Middle East for example. Every country in the Arab Middle East – and I’ve actually graphed this with peak water, and now it’s being followed by peak grain – it’s just going down very fast. The Saudis have declared that by next year, 2016 they will be out of agriculture entirely because all of the aquifers will have been pumped dry. Then the decline in irrigation and in food production will forces them into the world market. Now, because they’re a small country they’re not going to overwhelm the world market. But some of the larger countries like China or India are in this situation then we’ll see the pressure begin to build on world grain supplies because of the constraints composed by water shortages.

So if we have to discuss a topic at the Expo in Milan, about nourishing the planet, then, water is the topic to debate.

I think it is. For example, at Stanford they selected 600 agricultural counties in the US, and each county has it’s own data for grain production, and they also record temperatures. So what they did was to look at all of these counties and the yields each year, and the relations with temperature, and what they concluded was that a 1 degree Celsius rise in temperature reduces the grain harvest by 17 percent. Now keep in mind that the projections by meteorologists for the world are that there will be a 6 degree Celsius rise in temperature if we continue with business as usual. If a 1 degree Celsius rise in temperature reduces the harvest by 17 percent, imagine if that goes to 2 or 3 or 6 degrees Celsius.

So we’re facing some unprecedented challenges. Individual countries have had agricultural problems before because of drought or crop diseases or floods or what have you, but now it’s the world.

The other thing that’s happening is that there are about – I estimate – 3 billion people in the world who want to move up the food chain, and that means consuming more meat, milk, and eggs – which takes grain. In the US we consume say 1,600 pounds of grain per year. Most of that is in meat, milk and eggs – only a small fraction is breakfast cereal and bread and pastry and so on. In India it is 400 pounds per person, per year. Only one fourth. When you only have 400 pounds of grain per person, per year, that’s a pound a day, you can’t afford to convert much into animal protein. You need just that much to keep body and soul together. So that gives a sense of what happens when incomes in India start rising and they start eating more milk and eggs. For religious reasons they may not consume huge amounts of additional meat, as China is doing, but they will be consuming more milk and dairy products, and eggs – and that all takes grain.

The rule of thumb incidentally for converting grain into meat in a feedlot with steers is about 700 pounds of grain per pound of additional weight in terms of growth of the steer. For pigs it’s more like 3-4 pounds of grain per pound of additional pork. With poultry it’s less than 2 pounds of grain per pound of additional meat. With catfish it’s almost down to 1 to 1 because some species of catfish are bottom feeders, some feed on the vegetation. This is one reason why we’re seeing the enormous growth of fish farming in China.

How are we exploiting the land?

One of the things contributing to that is the huge growth in demand with the soybeans. Whether you’re feeding pigs or chickens or steers in the feedlot, the standard mix for feed for livestock and poultry is 1 part grain, 4 parts soybean meal. The high quality protein in the soybean meal allows livestock and poultry to convert grain and animal protein more efficiently than if they had an all grain diet. Then the question is how do we get the soybeans? In the Western hemisphere today, Argentina, Brazil, all the way up to the US and Canada, there is now more land in soybeans than either wheat or corn. Though the soybean originated in China, it produces maybe 13 million tons of soybeans a year. United States produces 85 million tons; Brazil produces 85 or 90 million tons. Most of the world soybean supply comes from the western hemisphere. Most of it – probably 90% of it. Thas require soil.

|

|

Lester Brown in India, 1956

|

What would your message for the Expo be?

One: we’ve got to revisit the population issue. Populations can’t keep growing indefinitely. We’ve got to begin coordinating population policy with water policy, for example.

So we have to start to talk again about the population issue.

No question. That’s one thing. Another thing is moving up the food chain. Many Americans have moved far enough up the food chain that they’re not only consuming excessive amounts of meat and milk and eggs, but they’re also negatively affecting their health. Too much animal fat in the diet. By moving down the food chain in a country like the United States, we can both simultaneously improve our health, and that of the planet because we lessen the stress on the earth’s land resources.

Third: concentrating on the water issue and how to stabilize the water situation, and how to use water more efficiently. This applies particularly to irrigation, because 80% of the water that we take from rivers or pump from underground is used for irrigation in the world. So irrigation efficiency becomes the key. That’s not just the irrigation system itself – it’s the water intensity of the crops that are growing. This is nourishing the planet.