|

|

|

Already the Dada avant guarde – in particolar Duchamp Ready Made – with an irreverent and liberating approach towards institutional art redefined the meaning of objects and images rejecting their original context and function.

Then, in the late 1950s, New Dada and Nouveaux Réalisme artists revisited the notion of Ready Made reappropriating everything society had to offer. So, not just products, but also waste. With a new “perceptive approach to reality” the former exalted the economic boom of those years transforming waste into works of art. In this way, ordinary waste and objects became art material in their own right.

And nowadays art tackles impacts produced by economic policies on the planet’s ecosystem and our own very survival. Artists become the spokespeople of a condemnation dictating a critical reflection, revisiting our society’s contradictions and lifestyles, encouraging a more conscientious worldview. Thus recycling and artistic creations share the same objective: to give a new life to previously used materials. At times it is a mere conceptual operation embedded in the work of art. On other occasions, it is a more concrete manifestation where the artist uses recycling as a creative method.

For instance, Forever bicycles by Chinese Ai Weiwei offers food for thought on pullution and lifestyle. Forever bicyles consists of thousands of bicycles, in a tribute to mass mobility. Ai Weiwei reiterates Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel highliting the importance of expanding our viewpoint on reality: it spurs us to observe how a bicycle can become an object that, paralysed in their entanglement with others, loses its integrity and function, where the sense of movement is achieved only by the optic illusion of superimposition. Oftetimes Ai Weiwei works encourage pondering on the value of individuals amongst the complexity of the social system; in Forever bicycles such reflection bonds with the theme of ecological impacts, of everyday habits and the pace of contemporary cities.

These very issues are conjured up, or rather claimed, albeit with a different language, in the works by Yuri Romagnoli, aka Hopnn. For this street artist, the ecological revolution takes place in the forms and colours of the urban space: Hopnn’s work on a wall or a burnt car’s body tells stories intended to inspire the use of bicycles instead of cars. Bicycles become a symbol of a new way to experience cities, they express the personal choice not to pollute (expressed in the slogan +B.C. = -CO2) and to put community welfare before individual advantages. The very aesthetics of bicycles contrasts with urban traffic’s industrial alienation, in head-on clashes where cars are wrecked, while a myriad of cyclists take flight.

In 2013, Hopnn dealt with the theme of waste and recycling during Paris Tour 13, when in the apartment 931 used the abandoned living space by transforming in a huge tricycle the dismantled parquet floor. A surprising and ephemeral sculpture that does not hide the recovered material it is made with.

|

|

Hopnn, Untitled – Tricycle, 2013, Tour 13, Paris

|

|

|

Hopnn, Spintime, 2015, Rome

|

|

|

Hopnn, Car, 2016, Trapani area Hopnn’s website, hopnn.com

|

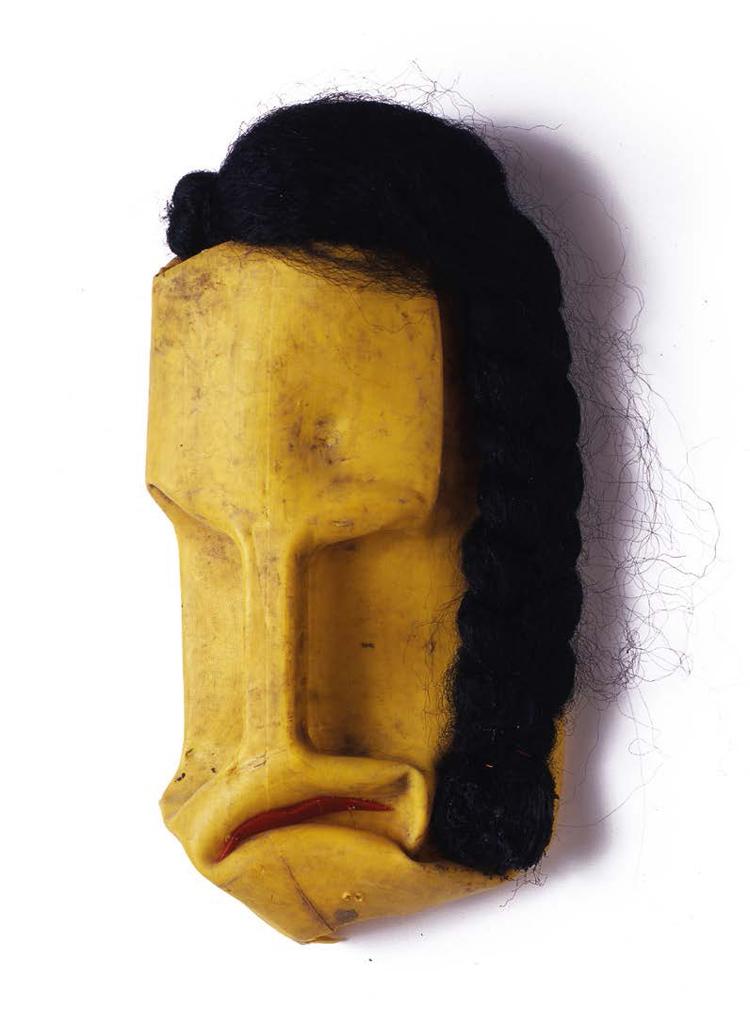

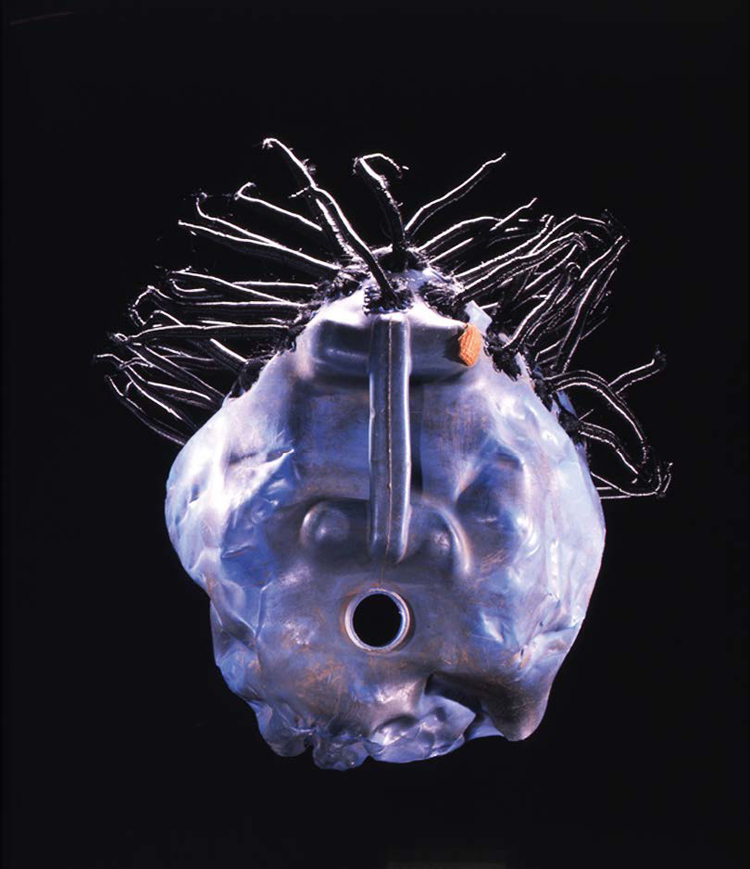

Benin-born Hazoumé is another example of how art, thanks to recycling, can draw inspiration from reality. With his masques-bidons made with jerrycans, tha artist talks of a world where human portraits become a simulacrum of oil trafficking between Benin and Nigeria, a symbol of corruption and economic-political inequality between Africa and the West. A conflict that takes shape in the portrait gallery the artist has been organizing for over twenty years. Each mask – despite the standard matrix dictated by jerrytanks – shows a character, a personality and uniqueness expressed through colours, engravings, writings on its skin. Suffice it to look at Ati and Miss Havana’s sculptures to realize how, starting from the very material, the artist is able to manipulate waste, creating characters while telling culture, traditions and contemporay Africa’s current events.

|

|

Romuald Hazoumé, Miss Havana, 1999, Plastic can, synthetic hair, copper

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

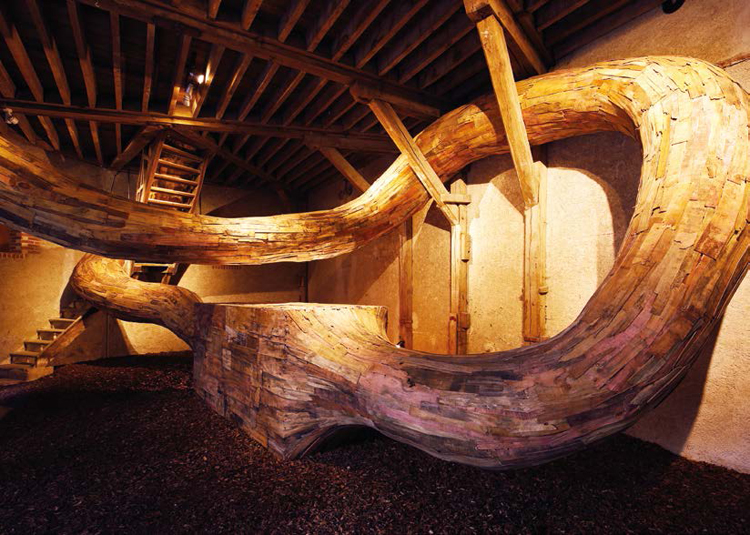

To focus the attention on how man interferes with nature, in a recycle of death and rebirth, Brazilian artist Henrique Oliveira uses wood instead. Baitogogo’s curvy and monstruous branches or whole tree trunks spring from the white wall of the White Cube freezing environment at Palais de Tokyo in Paris. Or from the warm atmosphere of the former Chaumont-sur-Loire chateau’s former barn with Momento Fecundo. Actually, these twisted trees are made with wood panels and planks recovered next to Rio’s building sites and favelas. The artist then reuses them so that matter riappropriates the shape nature had given it and the wood is reunited with its tree form.

These are manipulations combining the art of recycling and the act of giving back to the world through waste itself the evolution of lives and things living on it. The cycle of wood lived through its three phases – nature, object and community – is a critical and poetic reflection of what happened and continues to happen in our society, leaving us hope that art can give rise to a collective thought that is aware of its own very actions in the world.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|