In recent years the concept of Circular Economy has received growing attention, both in the worlds of science and of policy making. Some scholars and practitioners present it as a novelty, but we have to acknowledge that it builds on the legacy of predecessors, like waste recycling and separation, industrial ecology, eco-industrial parks and industrial symbiosis. Various concepts go back to the 1980’s, such as the concepts of waste hierarchies (3R’s, 4R’s etc.) and cascading. The 3R’s concept has become commonplace in many national waste regulations all over the world.

At best, we can frame the renewed attention as Circular Economy 3.0. By doing so, questions arise concerning what it takes from versions 1.0 and 2.0 and what is new. The “action imperatives” suggested by scientists may be the most important element: what should producers actually do to achieve the greatest impact. These have traditionally been expressed as the various R’s, complemented with expressions of preference and priority.

A remarkable finding emerging from extensive literature review from various disciplinary backgrounds (including environmental sciences, engineering, logistics, policy studies and more), is that in the literature there is a messy cacophony around the 3 or more R’s as value retention imperatives (we would prefer not to use the word “recycling” anymore as an overarching concept, as can be seen in the article). In explaining what to do, these authors present a range from 3Rs to 10R’s, with the 5R’s version being the most frequently suggested. In a similar analysis of 114 definitions we also illustrated the confusion around the conceptualisation of circular economy (Kirchherr et al. 2017).

|

|

R0 --> R9: Hierarchy of CE value retention options (RO’s) for consumers and businesses R0 = Refuse |

|

|

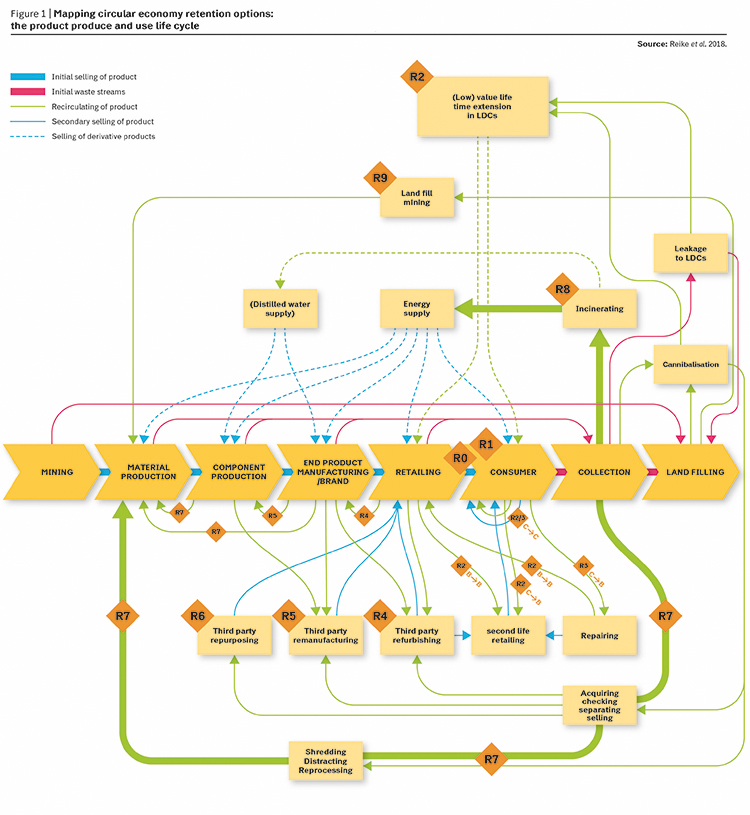

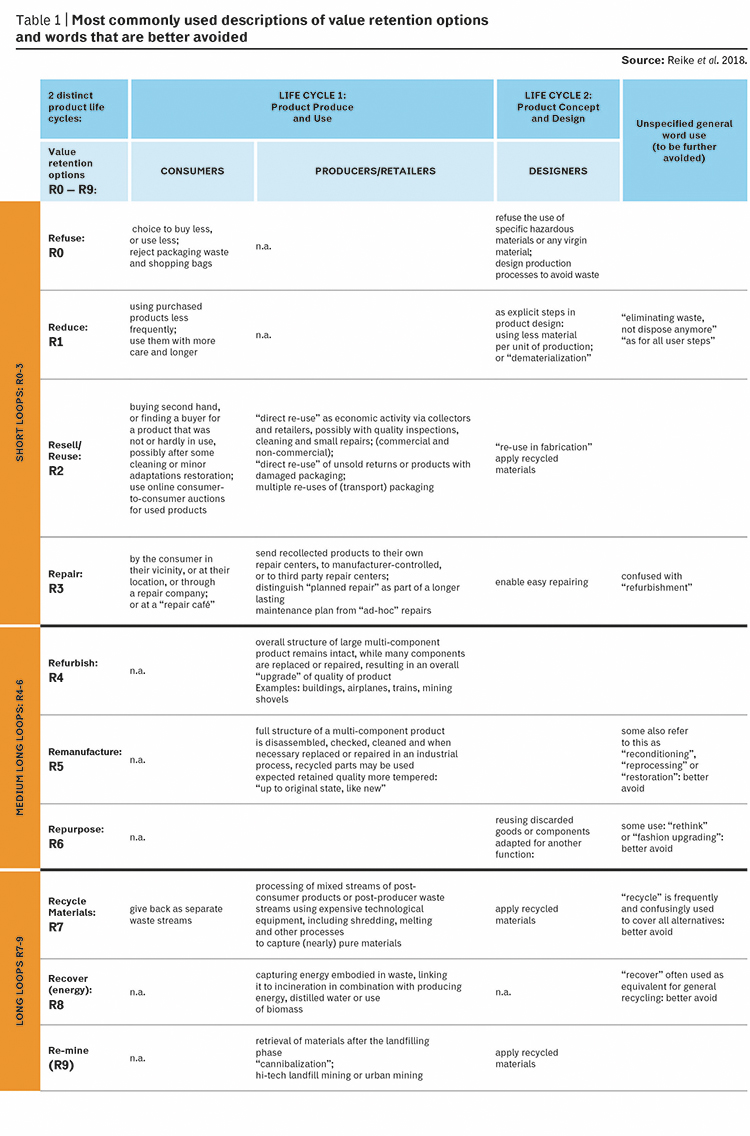

Table 1 Provides the main lessons from this analysis, which we suggest using as a guide for the future. In doing so, we need to distinguish between two types of product life cycles: we need to distinguish between the product life cycles of “Produce and Use” and of “Concept and Design.” Not doing so leads to part of the confusion as they refer to different actors and options. In Figure 1 we show the synthesis as the comprehensive Product Produce and Use Life Cycle (the second product life cycle is shown in Reike et al. 2018). |

We also see the same confusion in policy documents: both the EU and the UN suggest a 3R’s approach, but the R’s have different meanings. This links to a more serious issue in the scientific literature on circular economy: when using a 3R’s to 10R’s waste hierarchy, scientists are messing up still further because they use 38 different “re”-words in these hierarchies, even the one’s using 3R’s or 4R’s do not refer to the same R’s.

It is therefore necessary to clean up this conceptual confusion as much as possible. Synthesising the many contributions, we present a final 10R’s hierarchy (starting with the R0, being “refuse” from the consumer perspective, and ending up with R9, the re-mining from old land-fills).

With this, we present an integrated version of value retention options mapping, including some of the loops that are often ignored (like the substantial leakages to less developed countries – LDCs) and highlight the role of new economic actors in the repairing, refurnishing and remarketing of products. The figure allows balanced attention to be given to (in many places already well-organised) longer-value retention loops, middle long loops (where we now see many new business models initiated) and short loops (with a key role for consumers and non-commercial activities). This analysis stresses the distinction between short loops, middle-long loops and long loops.

The first four short loops (R0-3) exist close to the consumer, and can be linked to commercial or non- commercial actors engaged in extending the life span of the product. Scholars applying a clear hierarchy characterise these as the most preferable R’s in the circular economy. In our historic overview in the article, we argue that the varying emphasis on the R0 and R1 in the literature may be evidence of a paradigmatic division with respect to the issue of the perceived necessity of absolute reduction of inputs and consumption, and may hence also be related to the different motives of different groups in promoting circular economy. This may conflict with a current popular focus on business opportunities in the circular economy.

The second group of three medium-long loops (R4-6) includes refurbish, remanufacture and repurpose, often confused with each other and some other concepts. For these loops commercial business activity is the main driving force, with frequently specialised 3rd actors with high levels of expertise as stakeholders.

The third group of three long loops (R7-9) refer to traditional waste management activities, including recycling, different forms of energy recovery and, more recently, re-mining. Many scholars applying clear hierarchies with their R’s agree that these options are the least desirable. Still, materials or particles obtained through longer loop recycling can serve as input for shorter loop R’s (see “remanufacture”). This is also the area where government policies in the circular economy 1.0 and 2.0 have been focusing on. Here a key challenge is how higher-value application of recycled materials can be achieved, especially in the countries where mass recycling is already well organised (mostly in North-west and central Europe).

International Sustainable Development Research Society, http://isdrs.org

Copernicus Institute for Sustainable Development, www.uu.nl/en/research/copernicus-institute-of-sustainable-development

Kirchherr, J., Reike, D. & Hekkert, M., 2017, “Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions”, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 127, pp.221-232; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.005

Reike, D., Vermeulen, W.J.V. & Witjes, S., 2018, “The circular economy: New or Refurbished as CE 3.0? — Exploring Controversies in the Conceptualization of the Circular Economy through a Focus on History and Resource Value Retention Options”, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 135, pp.246-264; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.08.027

This is a re-print of an earlier online contribution to the CEC4Europe Factbook at www.cec4europe.eu/publications